Modernity, Now What? (part five, preface)

A Timeline of the Avant-garde

The following is my initial notes and organizing for a future text on the Avant-garde using Wiki as a start by forming a timeline. Enjoy…

What is the Avant-garde?

Revolt, protest, law breaking, canon braking, & banned books

Experimentation, & improvisation

Secret societies, & manifestos

Signs and symbols, magic, romanticism, & death

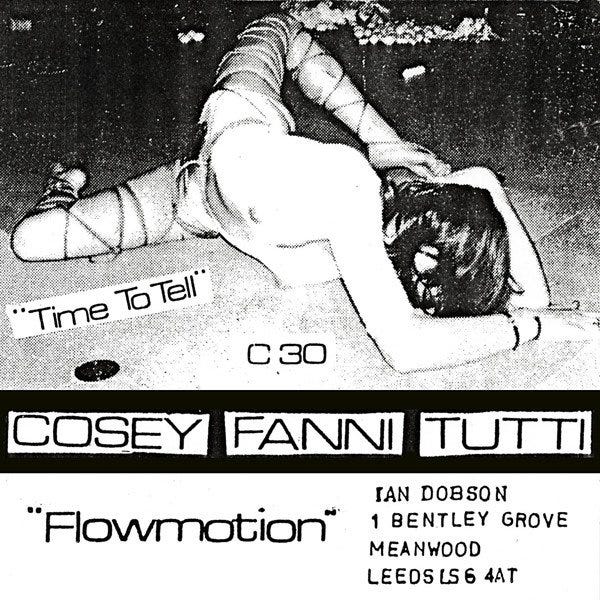

Queer, sex, nude, bondage, S&M, & burlesque

Bohemianism, drugs, libertines, Absinthe, & speakeasies

The New? Sometimes

The “Intelligentsia”? sometimes

Origin of the term: avant-garde

In the essay "The Artist, the Scientist, and the Industrialist" (1825) Benjamin Olinde Rodrigues's political usage of vanguard identified the moral obligation of artists to "serve as [the] avant-garde" of the people, because "the power of the arts is, indeed, the most immediate and fastest way" to realize social, political, and economic reforms.[4]

The French military term avant-garde (advanced guard) identified a reconnaissance unit who scouted the terrain ahead of the main force of the army. In 19th-century French politics, the term avant-garde (vanguard) identified Left-wing political reformists who agitated for radical political change in French society.

In the mid-19th century, as a cultural term, avant-garde identified a genre of art that advocated art-as-politics, art as an aesthetic and political means for realizing social change in a society.

Since the 20th century, the art term avant-garde identifies a stratum of the Intelligentsia that comprises novelists and writers, artists and architects et al. whose creative perspectives, ideas, and experimental artworks challenge the cultural values of contemporary bourgeois society.[7]

In the U.S. of the 1960s, the post–WWII changes to American culture and society allowed avant-garde artists to produce works of art that addressed the matters of the day, usually in political and sociological opposition to the cultural conformity inherent to popular culture and to consumerism as a way of life and as a worldview.[8]

In the essay "Avant-Garde and Kitsch" (1939), Clement Greenberg said that the artistic vanguard oppose high culture and reject the artifice of mass culture, because the avant-garde functionally oppose the dumbing down of society — be it with low culture or with high culture. That in a capitalist society each medium of mass communication is a factory producing artworks, and is not a legitimate artistic medium; therefore, the products of mass culture are kitsch, simulations and simulacra of Art.[14]

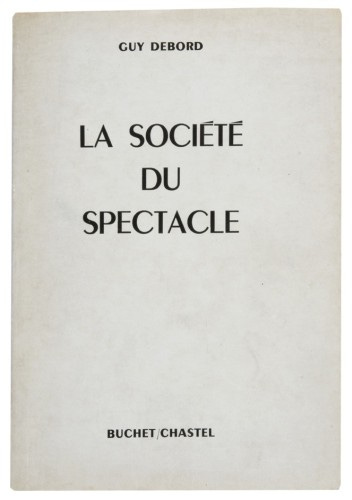

In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord said that the financial, commercial, and economic co-optation of the avant-garde into a commodity produced by neoliberal capitalism makes doubtful that avant-garde artists will remain culturally and intellectually relevant to their societies for preferring profit to cultural change and political progress.

Types of Avant-garde

· Art as an aesthetic and political means for realizing social change in a society.

· Experimental work of art, and the experimental artist who created the work of art, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable to the artistic establishment of the time.

· Intellectual

· The Underground, Sub-culture, Counter-culture

· Anti-art

Against the Academy and High Culture, 1789-1918

· Red Carpets, Haute Couture, High Society

· Imperial Modernity: Academies, Institutes, Salons, the Canon

· Ballet, Opera, Theater, Symphony, Neoclassicism

· Académie des Beaux-Arts

· Academic Art: History Painting, Portrait art, Genre Painting, Landscape Art, Still Life Painting

A Timeline of the Avant-Garde

Pornography and Satire

Fanny Hill (1748), considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel," has been one of the most prosecuted and banned books.

1777-1790, Marquise De Sade, The 120 Days of Sodom, Justine, Juliette and Philosophy in the Bedroom

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjectivity, imagination, and appreciation of nature in society and culture in response to the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

Romanticists rejected the social conventions of the time in favour of a moral outlook known as individualism. They argued that passion and intuition were crucial to understanding the world, and that beauty is more than merely an affair of form, but rather something that evokes a strong emotional response. With this philosophical foundation, the Romanticists elevated several key themes to which they were deeply committed: a reverence for nature and the supernatural, an idealization of the past as a nobler era, a fascination with the exotic and the mysterious, and a celebration of the heroic and the sublime.

Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror (primarily in the 20th century), is a literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name of the genre is derived from the Renaissance era use of the word "gothic", as a pejorative to mean medieval and barbaric, which itself originated from Gothic architecture and in turn the Goths.[1]

The first work to be labelled as Gothic was Horace Walpole's 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, later subtitled A Gothic Story. Subsequent 18th-century contributors included Clara Reeve, Ann Radcliffe, William Thomas Beckford, and Matthew Lewis. The Gothic influence continued into the early 19th century, with Romantic works by poets, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Lord Byron. Novelists such as Mary Shelley, Charles Maturin, Walter Scott and E. T. A. Hoffmann frequently drew upon gothic motifs in their works as well.

Gothic aesthetics continued to be used throughout the early Victorian period in novels by Charles Dickens, Brontë sisters, as well as works by the American writers, Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Later, Gothic fiction evolved through well-known works like Dracula by Bram Stoker, The Beetle by Richard Marsh, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. In the 20th-century, Gothic fiction remained influential with contributors including Daphne du Maurier, Stephen King, V. C. Andrews, Shirley Jackson, Anne Rice, and Toni Morrison.

1818, Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. Frankenstein tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment that involved putting it together with different body parts. Shelley started writing the story when she was 18 and staying in Bath, and the first edition was published anonymously in London on 1 January 1818, when she was 20. Her name first appeared in the second edition, which was published in Paris in 1821.

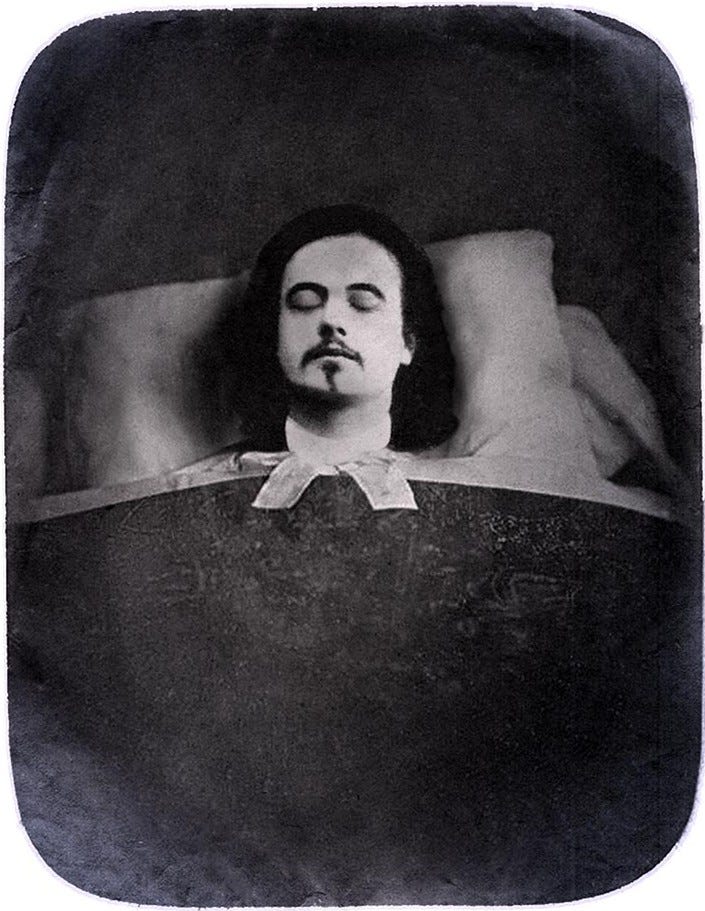

Edgar Allan Poe (né Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as one of the central figures of Romanticism and Gothic fiction in the United States and of early American literature.[1] Poe was one of the country's first successful practitioners of the short story, and is generally considered to be the inventor of the detective fiction genre. In addition, he is credited with contributing significantly to the emergence of science fiction.[2] He is the first well-known American writer to earn a living exclusively through writing, which resulted in a financially difficult life and career.[3]

drugs, bars, cafes

Bohemian is a 19th-century historical and literary topos that places the milieu of young metropolitan artists and intellectuals—particularly those of the Latin Quarter in Paris—in a context of poverty, hunger, appreciation of friendship, idealization of art and contempt for money. Based on this topos, the most diverse real-world subcultures are often referred to as "bohemian" in a figurative sense, especially (but by no means exclusively) if they show traits of a precariat.

The Vault at Pfaff's - An Archive of Art and Literature by the Bohemians of Antebellum New York

Drag clubs and Balls

As early as 1725, customers fought off a police raid at a London homosexual molly house.[18]

1869, Hamilton Lodge Ball, NYC

During the 1880s and 1890s, Swann organized a series of drag balls in Washington, D.C. He called himself the "queen of drag".[1] Most of the attendees of Swann's gatherings were men who were formerly enslaved who gathered to dance in their satin and silk dresses.[6] This group, consisting of "former slaves and rebel drag queens", was known as the "House of Swann".[7]

Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, unusual visual angles, and inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience. Impressionism originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s.

The Impressionists faced harsh opposition from the conventional art community in France. The name of the style derives from the title of a Claude Monet work, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satirical 1874 review of the First Impressionist Exhibition published in the Parisian newspaper Le Charivari.[1] The development of Impressionism in the visual arts was soon followed by analogous styles in other media that became known as Impressionist music and Impressionist literature.

1863, Salon des Refuses, the Paris Salon (1667) jury refused two thirds of the paintings presented, including the Impressionists works of Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Antoine Chintreuil, and Johan Jongkind. The rejected artists and their friends protested, and the protests reached Emperor Napoleon III.

Proto Surrealism

Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) is a French poetic novel, or a long prose poem. It was written and published between 1868 and 1869 by the Comte de Lautréamont, the nom de plume of the Uruguayan-born French writer Isidore Lucien Ducasse.[1] The work concerns the misanthropic, misotheistic character of Maldoror, a figure of evil who has renounced conventional morality.

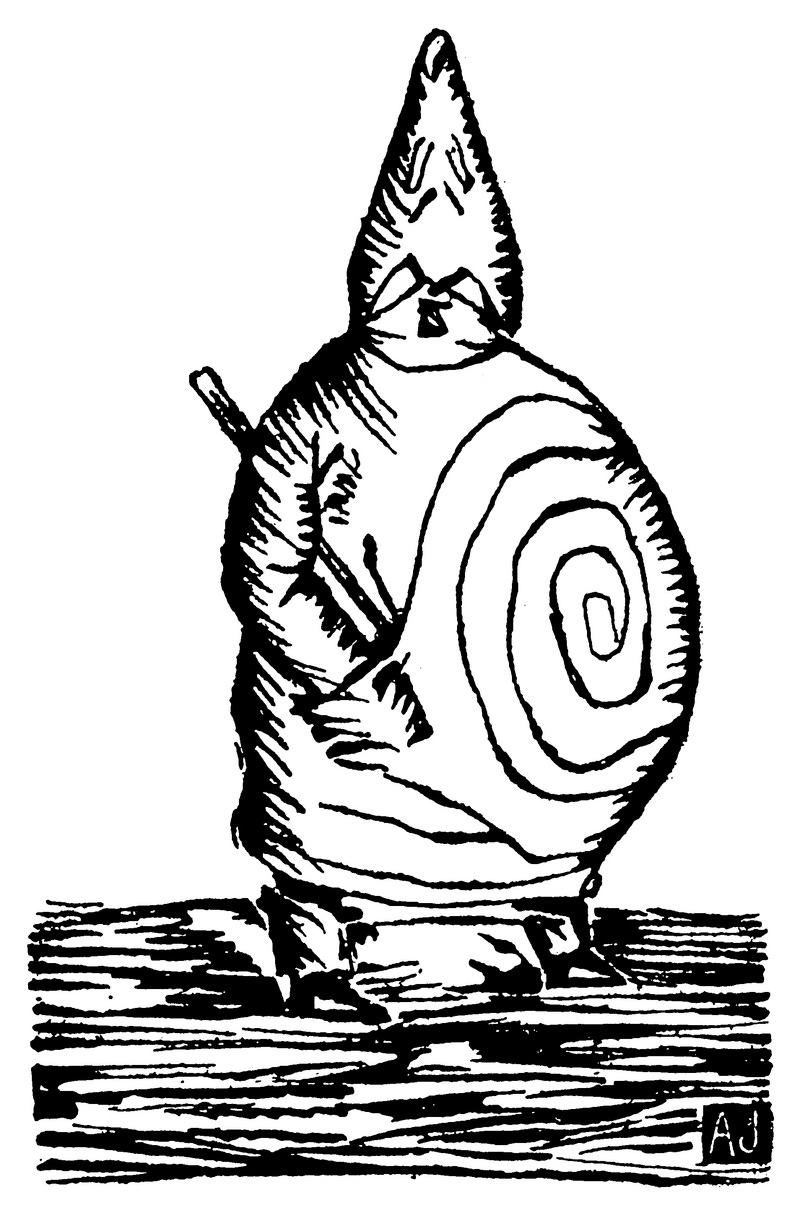

Alfred Jarry, (French: [al.fʁɛd ʒa.ʁi]; 8 September 1873 – 1 November 1907) was a French symbolist writer who is best known for his play Ubu Roi (1896), often cited as a forerunner of Dada and the Surrealist and Futurist movements of the 1920s and 1930s.[1][2] He also coined the term and philosophical concept of 'pataphysics.[3]

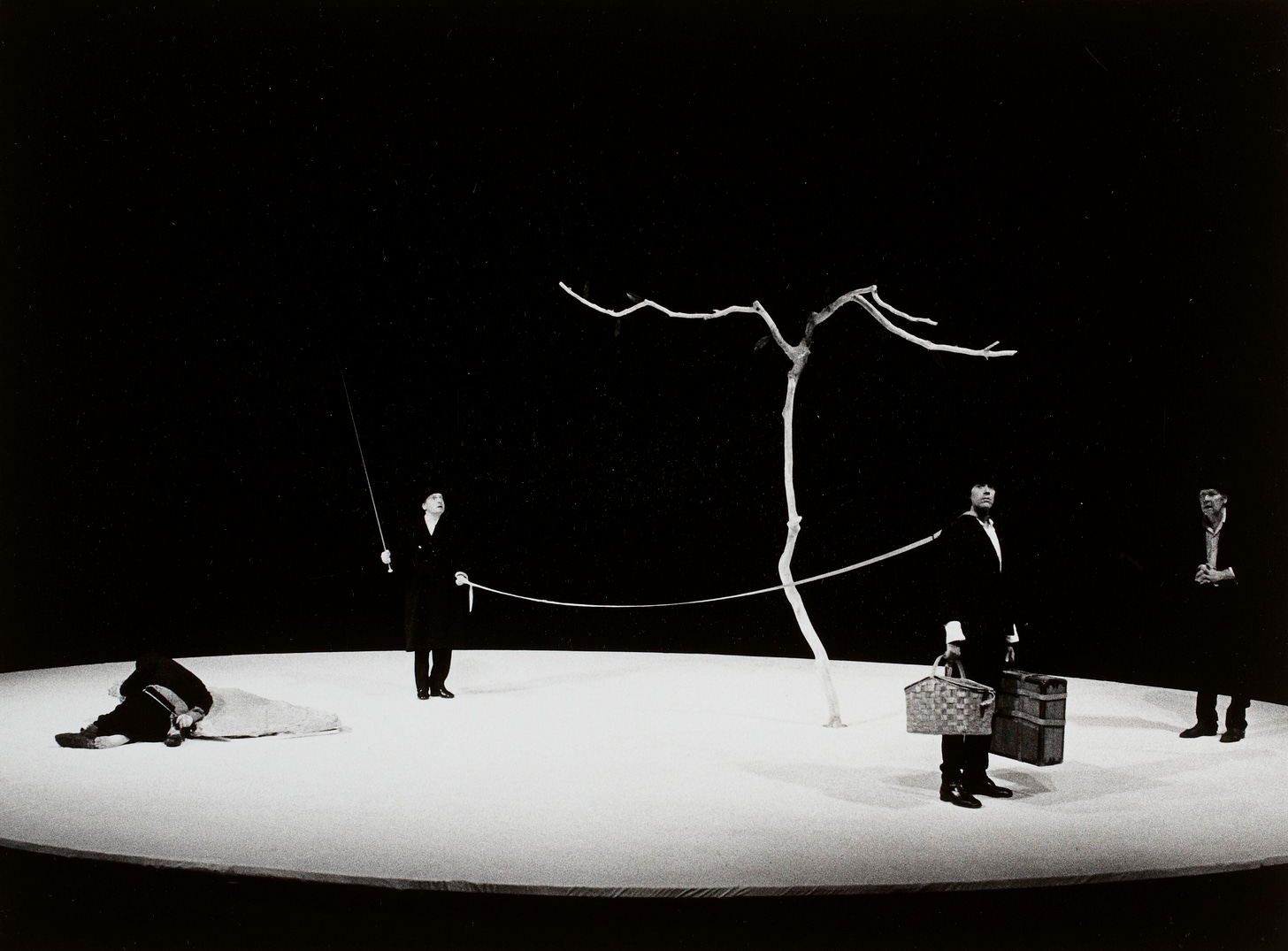

Ubu Roi ([yby ʁwa]; "Ubu the King" or "King Ubu") is a play by French writer Alfred Jarry, then 23 years old. It was first performed in Paris in 1896, by Aurélien Lugné-Poe's Théâtre de l'Œuvre at the Nouveau-Théâtre (today, the Théâtre de Paris). The production's single public performance baffled and offended audiences with its unruliness and obscenity. Considered to be a wild, bizarre and comic play, significant for the way it overturns cultural rules, norms and conventions, it is seen by 20th- and 21st-century scholars to have opened the door for what became known as modernism in the 20th century, and as a precursor to Dadaism, Surrealism and the Theatre of the Absurd.

1865, the US postal service was seen as a "vehicle" for the transmission of materials that were deemed obscene by the American lawmakers.[62]

The Paris Commune (French: Commune de Paris, pronounced [kɔ.myn də pa.ʁi]) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended Paris, and working-class radicalism grew among its soldiers. Following the establishment of the French Third Republic in September 1870 (under French chief-executive Adolphe Thiers from February 1871) and the complete defeat of the French Army by the Germans by March 1871, soldiers of the National Guard seized control of the city on 18 March. The Communards killed two French Army generals and refused to accept the authority of the Third Republic; instead, the radicals set about establishing their own independent government.

(1871, Le Commune, Paris) , Peter Watkins

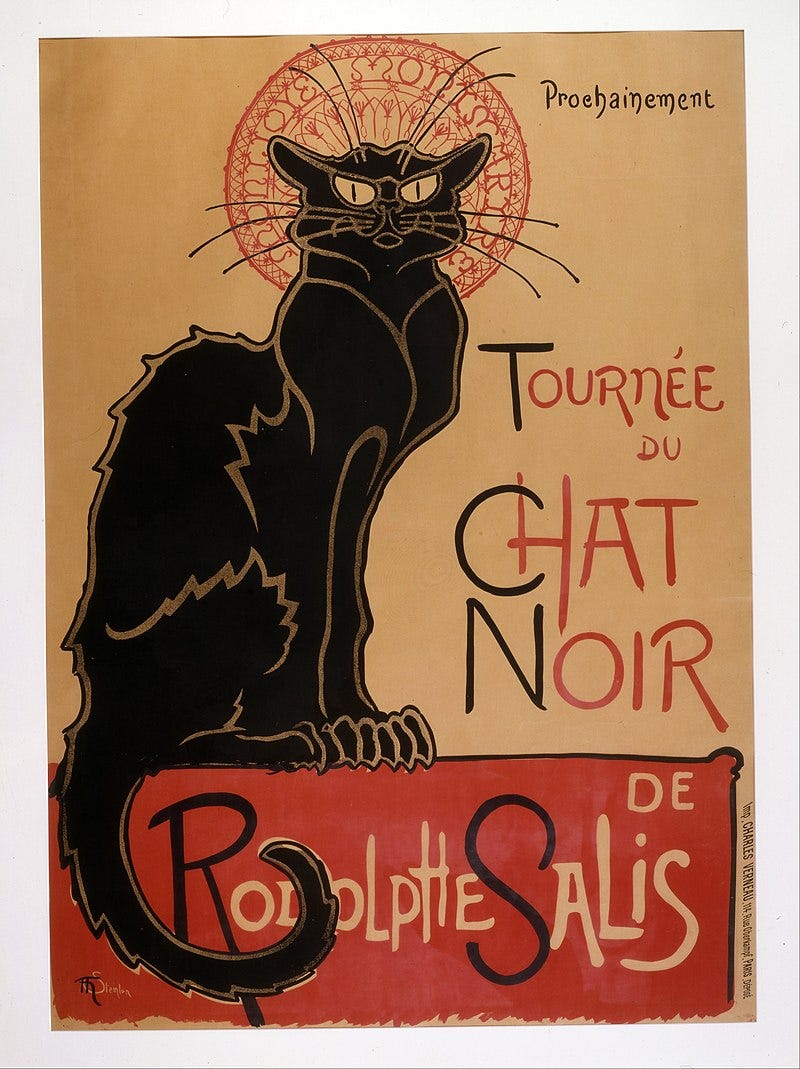

Le Chat Noir (French pronunciation: [lə ʃa nwaʁ]; French for "The Black Cat") was a 19th century entertainment establishment in the [1] Montmartre district of Paris. It was opened on 18 November 1881 at 84 Boulevard de Rochechouart by impresario Rodolphe Salis, and closed in 1897 not long after Salis' death. Le Chat Noir is thought to be the first modern cabaret:[2] a nightclub where the patrons sat at tables and drank alcoholic beverages while being entertained by a variety show on stage. The acts were introduced by a master of ceremonies who interacted with well-known patrons at the tables.

Moulin Rouge[1] (/ˌmuːlæ̃ ˈruːʒ/, French: [mulɛ̃ ʁuʒ]; lit. '"Red Mill"') is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche. In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Paris Olympia. The original venue was destroyed by fire in 1915, reopening in 1925 after rebuilding. Moulin Rouge is southwest of Montmartre, in the Paris district of Pigalle on Boulevard de Clichy in the 18th arrondissement, and has a landmark red windmill on its roof.

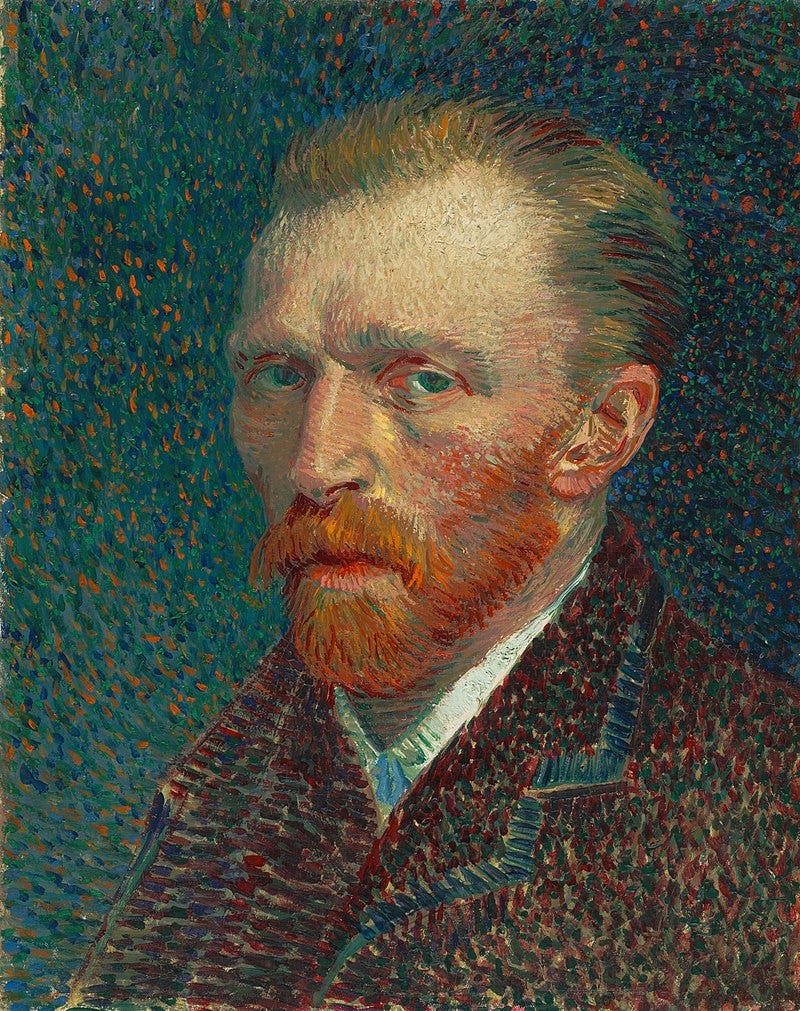

Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləɱ vɑŋ ˈɣɔx] ⓘ;[note 1] 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who is among the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade he created approximately 2100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of them in the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits, and are characterised by bold, symbolic colours, and dramatic, impulsive and highly expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. Only one of his paintings was known by name to have been sold during his lifetime. Van Gogh became famous after his suicide at age 37, which followed years of poverty and mental illness.

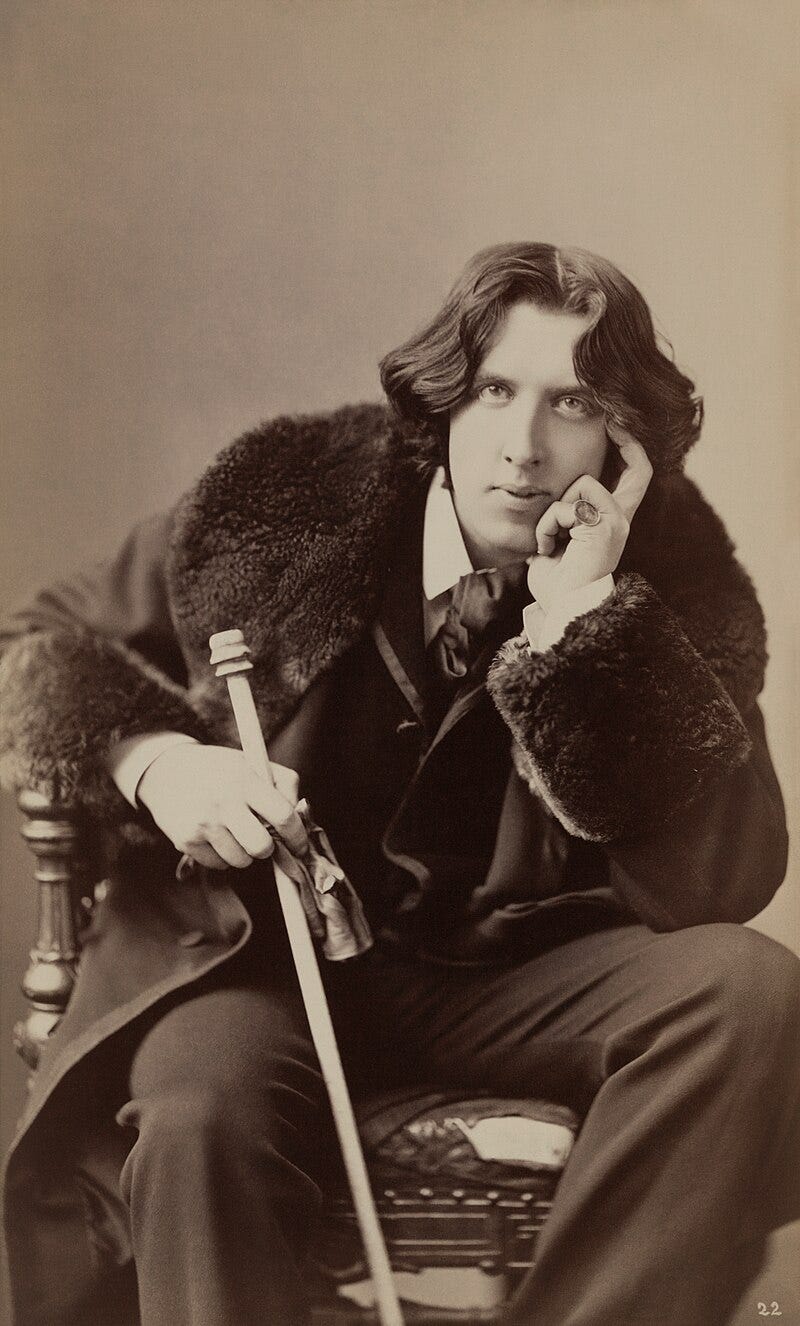

Oscar Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and his criminal conviction for gross indecency for homosexual acts.

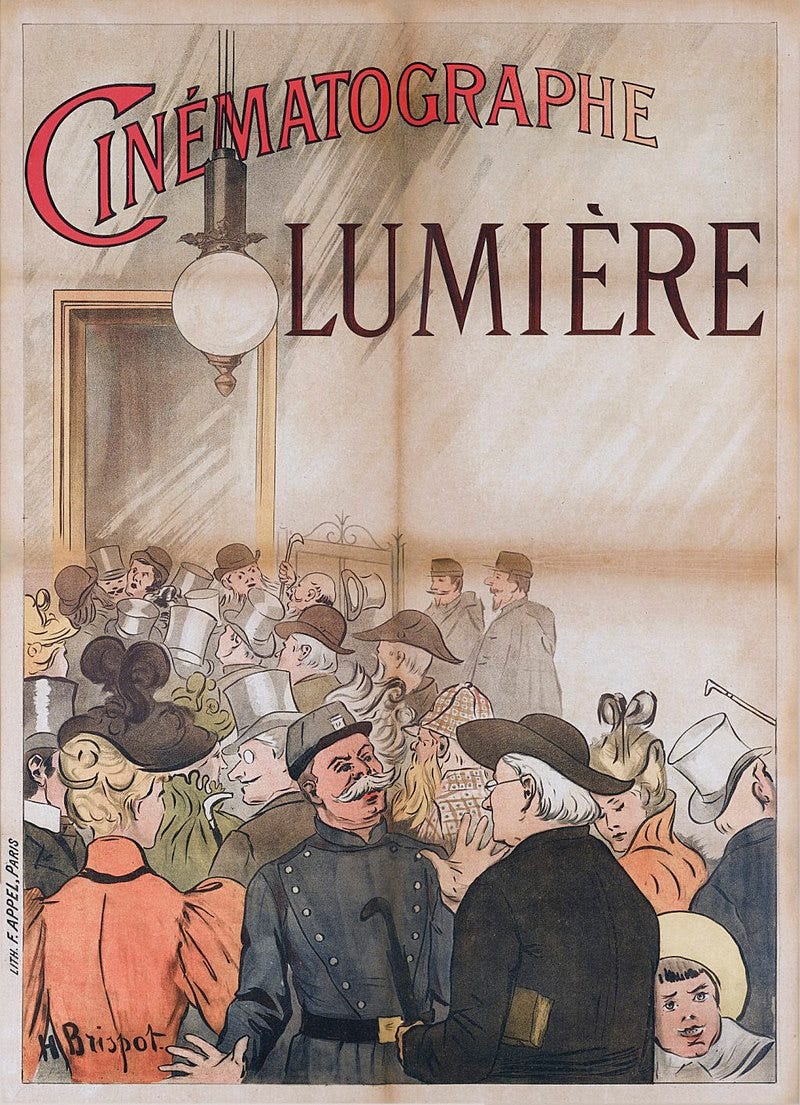

1895, first motion picture, French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière

On 22 March 1895, in Paris, at the Society for the Development of the National Industry, in front of a small audience, one of whom was said to be Léon Gaumont, then director of the company Comptoir Géneral de la Photographie, the Lumières privately screened a single film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory. The main focus of the conference by Louis concerned the recent developments in the photographic industry, mainly the research on polychromy (colour photography). It was much to Lumière's surprise that the moving black-and-white images retained more attention than the coloured stills.[10]

The Lumières gave their first paid public screening on 28 December 1895, at Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris.[11] This presentation consisted of the following 10 short films:[12][13]

La Sortie de l'usine Lumière à Lyon (literally, "the exit from the Lumière factory in Lyon", or, under its more common English title, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory), 46 seconds

La Voltige (Horse Trick Riders), 46 seconds

La Pêche aux poissons rouges ("fishing for goldfish"), 42 seconds

Le Débarquement du congrès de photographie à Lyon (The Photographical Congress Arrives in Lyon), 48 seconds

Les Forgerons (The Blacksmiths), 49 seconds

Le Jardinier (L'Arroseur Arrosé) (The Gardener, or The Sprinkler Sprinkled), 49 seconds

Repas de bébé (Baby's Breakfast (lit. "baby's meal")), 41 seconds

Le Saut à la couverture ("Jumping Onto the Blanket"), 41 seconds

Place des Cordeliers à Lyon (Cordeliers' Square in Lyon), 44 seconds

La Mer (The Sea), 38 seconds

The New, Modern Art Movements Prior to WWI

Romanticism, Realism, Pre-Raphaelites, Macchiaioli, Impressionism, Post-impressionism, Pointillism, Divisionism, Symbolism, Les Nabis, Art Nouveau, Auguste Rodin, Abstraction, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, Suprematism, Synchromism, Vorticism, Modern Sculpture

Marie Louise Fuller was born on January 15, 1862, in Fullersburg, Illinois, also known as Louie Fuller and Loïe Fuller, was an American dancer and a pioneer of modern dance and theatrical lighting techniques. Auguste Rodin said of her, "Loie Fuller has paved the way for the art of the future."[2]

Modern Dance: (Free Dance) Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, Ruth St. Denis; (Expressionists) Mary Wigman in Germany, Francois Delsarte, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (Eurhythmics), and Rudolf Laban; Ted Shawn, Eleanor King, Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Katherine Dunham, Charles Weidman, Lester Horton, José Limón, Pearl Primus, Merce Cunningham, Talley Beatty, Erick Hawkins, Anna Sokolow, Anna Halprin, Paul Taylor, Judson Dance Theater (PM), Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti.

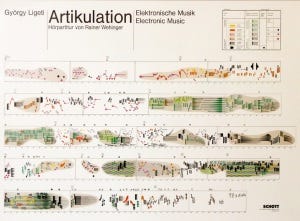

Atonal music (1907), Arnold Schoenberg, twelve-tone technique, an influential compositional method of manipulating an ordered series of all twelve notes in the chromatic scale.

World Wars as leaders of two radically different approaches to writing modern music. Not only rivals, they personally despised each other.

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky[a] (17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and United States citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music.

The Rite of Spring (French: Le Sacre du printemps) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1913 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; the original choreography was by Vaslav Nijinsky with stage designs and costumes by Nicholas Roerich. When first performed at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 29 May 1913, the avant-garde nature of the music and choreography caused a sensation. Many have called the first-night reaction a "riot" or "near-riot", though this wording did not come about until reviews of later performances in 1924, over a decade later.[1]

ErikSatie, (17 May 1866 – 1 July 1925), who signed his name Erik Satie after 1884, was a French composer and pianist. He was the son of a French father and a British mother. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire, but was an undistinguished student and obtained no diploma. In the 1880s he worked as a pianist in café-cabaret in Montmartre, Paris, and began composing works, mostly for solo piano, such as his Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes. He also wrote music for a Rosicrucian sect to which he was briefly attached.

Avant-garde music, some avant-garde composers of the 20th century include Arnold Schoenberg,[29] Richard Strauss (in his earliest work),[30] Charles Ives,[31] Igor Stravinsky,[29] Anton Webern,[32] Edgard Varèse, Alban Berg,[32] George Antheil (in his earliest works only), Henry Cowell (in his earliest works), Harry Partch, John Cage, Iannis Xenakis,[29] Morton Feldman, Karlheinz Stockhausen,[33] Pauline Oliveros,[34] Philip Glass, Meredith Monk,[34] Laurie Anderson,[34] and Diamanda Galás.[34]

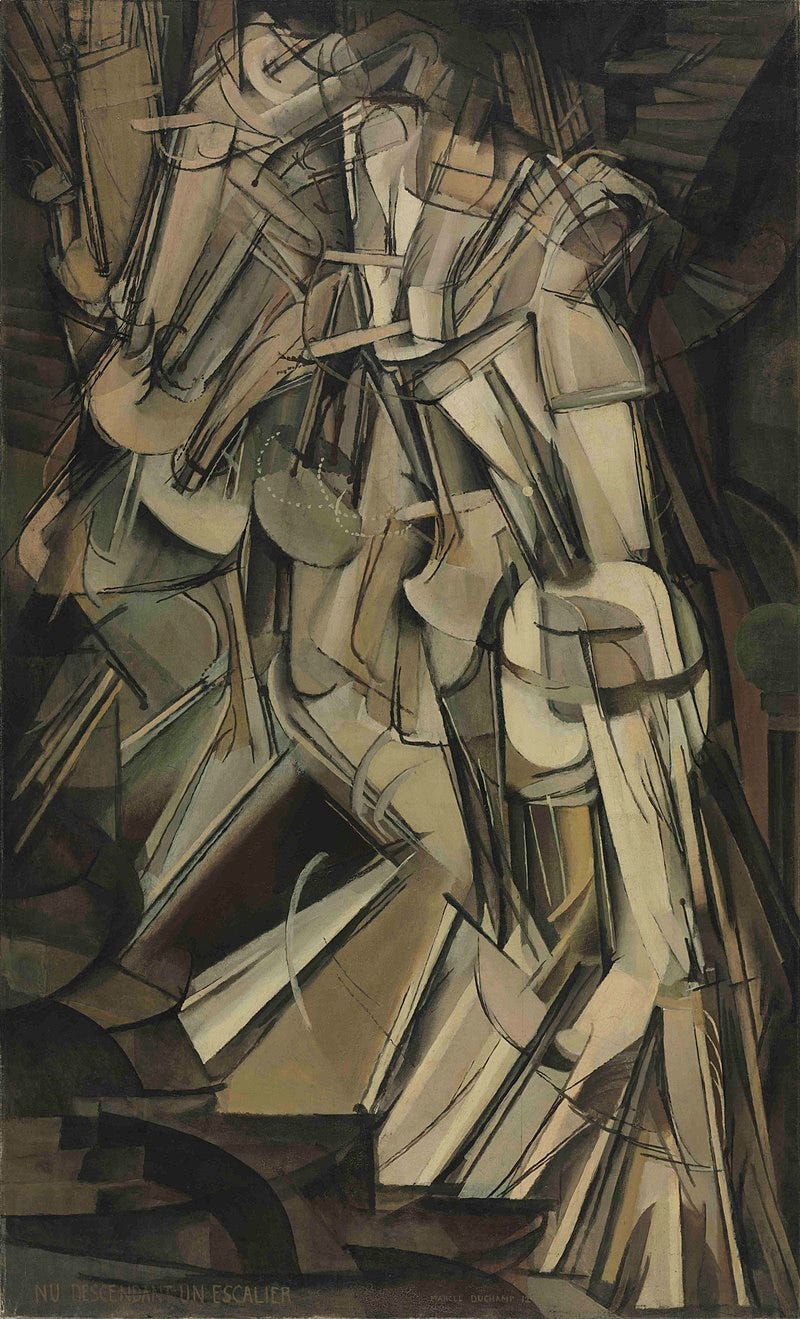

The 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of the many exhibitions that have been held in the vast spaces of U.S. National Guard armories.

New Modern Art Movements between WWI & WWII

Dada, Surrealism, Expressionism, Pittura Metafisica, De Stijil, New Objectivity, Figurative painting, American Modernism, Constructivism, Bauhaus, Scottish Colorists, Social Realism, Boychukism

DADA, Anti-art

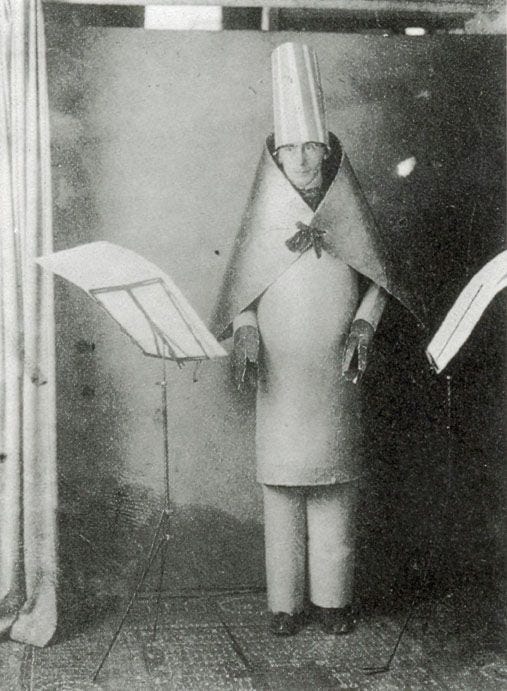

DADA with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916), founded by Hugo Ball with his companion Emmy Hennings, and in Berlin in 1917.[2][3] New York Dada began c. 1915,[4][5] and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted until the mid 1920s.

Duchamp, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Richard Huelsenbeck, Georg Grosz, John Heartfield, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters, and Hans Richter,

The movement influenced later styles, such as the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art, and Fluxus.

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp (UK: /ˈdjuːʃɒ̃/, US: /djuːˈʃɒ̃, djuːˈʃɑːmp/;[1] French: [maʁsɛl dyʃɑ̃]; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, Futurism and conceptual art.[2][3][4] He is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the 20th century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture.[5][6][7][8] He has had an immense impact on 20th- and 21st-century art, and a seminal influence on the development of conceptual art. By the time of World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists (such as Henri Matisse) as "retinal," intended only to please the eye. Instead, he wanted to use art to serve the mind.[9]

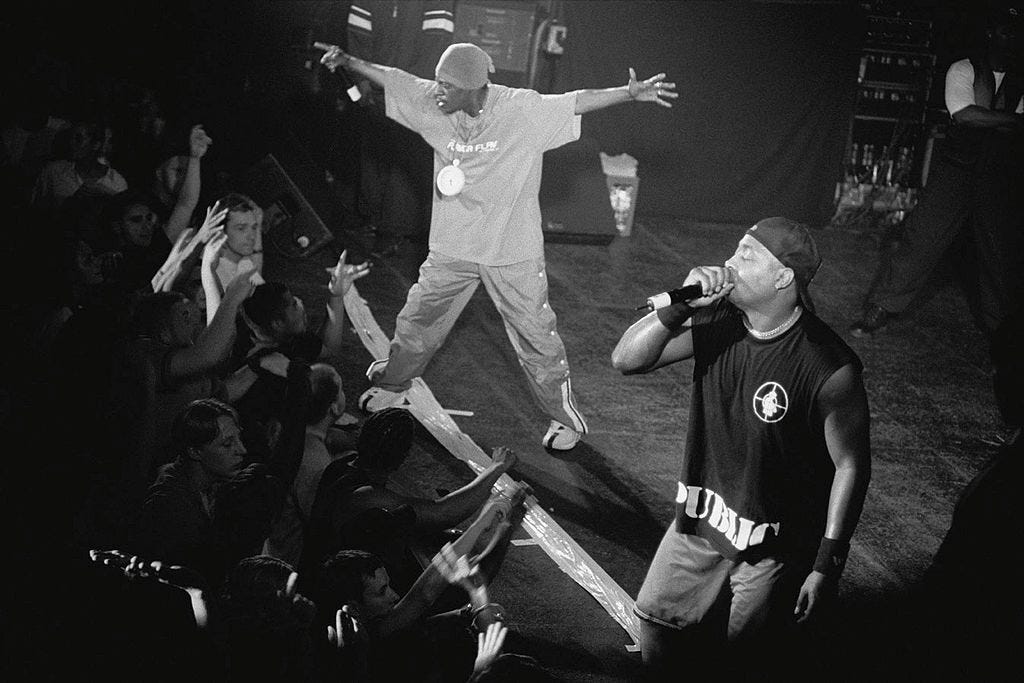

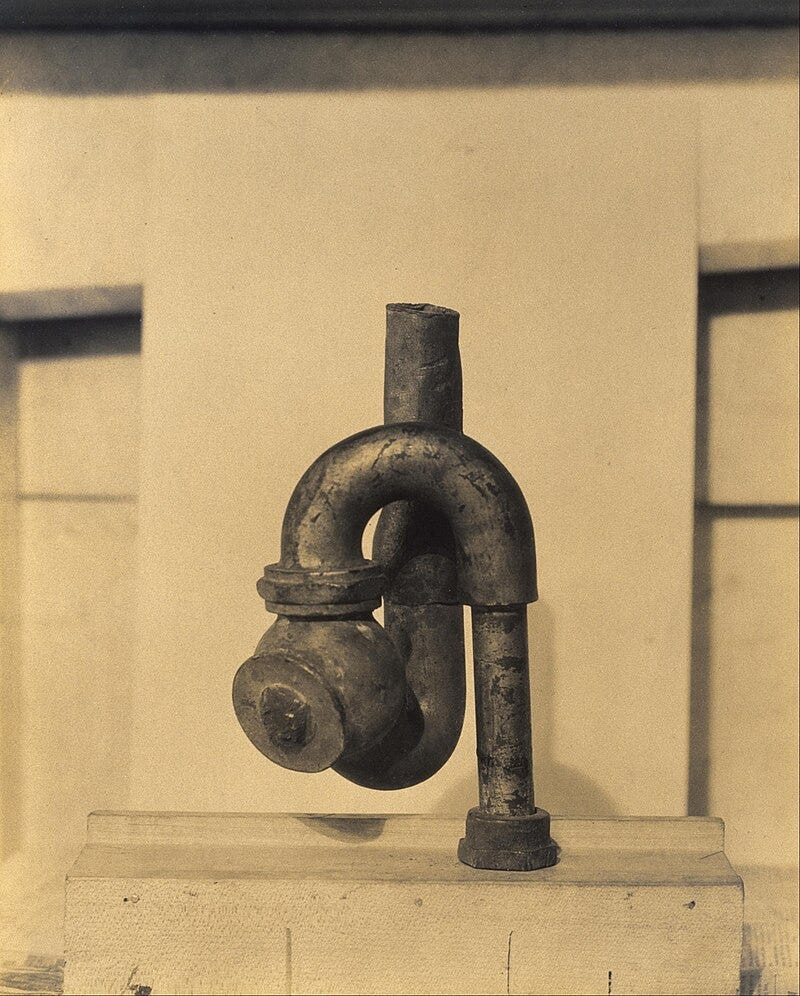

Duchamp is remembered as a pioneering figure partly because of the two famous scandals he provoked -- his Nude Descending a Staircase that was the most talked-about work of the landmark 1913 Armory Show -- and his Fountain, a signed urinal displayed in the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition that nearly single-handedly launched the New York Dada movement and led the entire[peacock prose] New York art world to ponder the question of "What is art?"

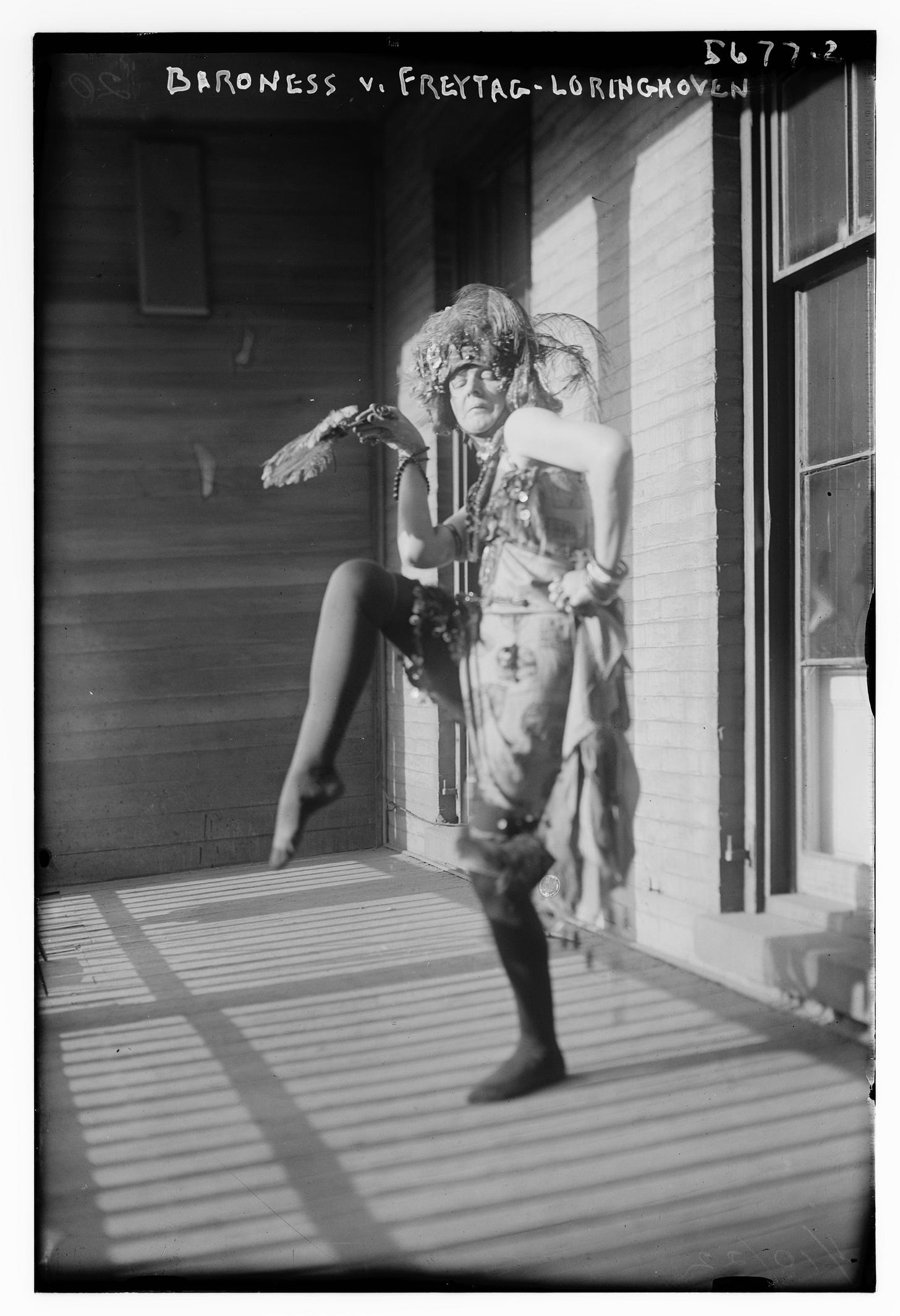

1917, The Fountain, attributed to Duchamp, most likely, was actually created by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists.

Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (née Else Hildegard Plötz; 12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927) was a German avant-garde visual artist and poet, who was active in Greenwich Village, New York, from 1913 to 1923, where her radical self-displays came to embody a living Dada. She was considered one of the most controversial and radical women artists of the era.

Stream of Conscious

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator.[1] It is usually in the form of an interior monologue which is disjointed or has irregular punctuation.[2] The term was first used in 1855 and was first applied to a literary technique in 1918. While critics have pointed to various literary precursors, it was not until the 20th century that this technique was fully developed by modernist writers such as Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Dorothy Richardson and Virginia Woolf.

1922, James Joyce's Ulysses (banned)

Marcel Proust is often presented as an early example of a writer using the stream of consciousness technique in his novel sequence À la recherche du temps perdu (1913–1927) (In Search of Lost Time)

Prominent uses in the years that followed the publication of James Joyce's Ulysses include Italo Svevo, La coscienza di Zeno (1923),[31] Virginia Woolf in Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927), and William Faulkner in The Sound and the Fury (1929).[32]

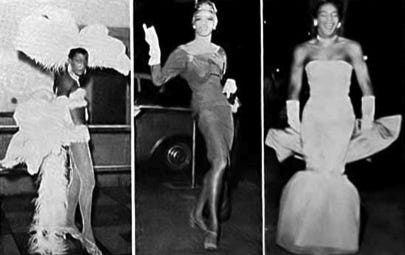

1920’s Drag Balls, Greenwich Village (Webster Hall), Harlem Renaissance

The Hamilton Lodge Ball, also known as the Masquerade and Civic Ball, was an annual cross-dressing ball in Harlem, United States. The Lodge's ball in 1869 was recognized as the first drag ball in United States history. The Hamilton Lodge Ball reached the peak of its popularity in the 1920s and early 1930s, as the Harlem Renaissance and Pansy Craze drew wealthy white New Yorkers and celebrities into Harlem nightlife. The Hamilton Lodge Ball drew hundreds of drag performers and thousands of spectators from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. While the Hamilton Ball was a rare scene of interracial nightlife, many of the performers were young, working class black men and women. Despite the unifying quality of the event that drew crowds across age, gender, race, and class, class divisions were apparent as performers were often less affluent than their wealthier elite audiences.[1] The balls featured a pageant contest in which drag performers competed for cash prizes. Prizes were awarded for most accurate cross dressing performance as well as best attire.[1]

Surrealism

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas.[1] Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality.[2][3]

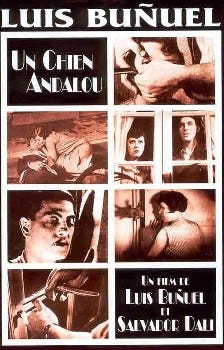

Surrealist Film, Dali vs Artaud

The Seashell and the Clergyman (French: La Coquille et le Clergyman) is a 1928 French experimental film directed by Germaine Dulac, from an original scenario by Antonin Artaud. It premiered in Paris on 9 February 1928. The film is associated with French Surrealism. The BFI included The Seashell and the Clergyman on a list of 10 Great Feminist Films, stating:[7]

Germaine Dulac was involved in the avant garde in Paris in the 1920s. Both The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922) and The Seashell and the Clergyman are important early examples of radical experimental feminist filmmaking, and provide an antidote to the art made by the surrealist brotherhood. The latter film, an interpretation of Anton Artaud’s book of the same name, is a visually imaginative critique of patriarchy – state and church – and of male sexuality. On its premiere, the surrealists greeted it with noisy derision, calling Dulac “une vache”.

Surrealist films of the twenties include René Clair's Entr'acte (1924), Fernand Léger's Ballet Mécanique (1924), Jean Renoir's La Fille de l'Eau (1924), Marcel Duchamp's Anemic Cinema (1926), Jean Epstein's Fall of the House of Usher (1928) (with Luis Buñuel assisting), Watson and Webber's Fall of the House of Usher (1928)[4] and Germaine Dulac's The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928) (from a screenplay by Antonin Artaud). Other films include Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L'Âge D'Or (1930), both by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí; Buñuel went on to direct many more films, never denying his surrealist roots.[5] Ingmar Bergman said "Buñuel nearly always made Buñuel films".[6]

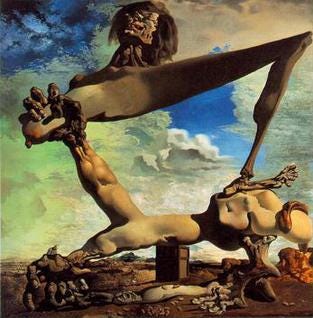

DALI, Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol[b][a] GYC (11 May 1904 – 23 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí (/ˈdɑːli, dɑːˈliː/ DAH-lee, dah-LEE;[2] Born in Figueres in Catalonia, Dalí received his formal education in fine arts in Madrid. Influenced by Impressionism and the Renaissance masters from a young age, he became increasingly attracted to Cubism and avant-garde movements.[3] He moved closer to Surrealism in the late 1920s and joined the Surrealist group in 1929, soon becoming one of its leading exponents. His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in August 1931. Dalí lived in France throughout the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939) before leaving for the United States in 1940 where he achieved commercial success. He returned to Spain in 1948 where he announced his return to the Catholic faith and developed his "nuclear mysticism" style, based on his interest in classicism, mysticism, and recent scientific developments.[4]

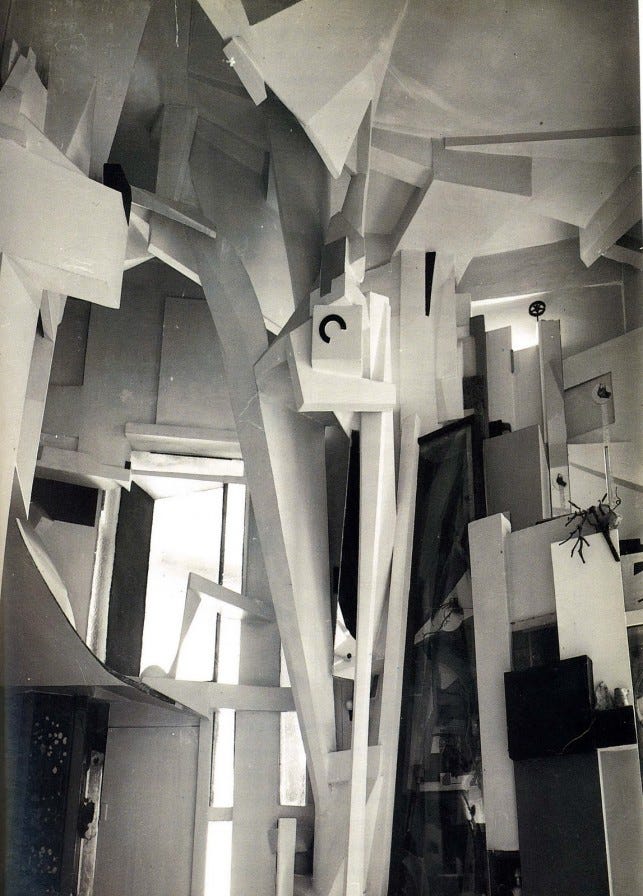

Kurt Schwitters, (20 June 1887 – 8 January 1948) was a German artist who was born in Hanover, Germany. Schwitters worked in several genres and media, including Dadaism, constructivism, surrealism, poetry, sound, painting, sculpture, graphic design, typography, and what came to be known as installation art. He is most famous for his collages, called "Merz Pictures".

Jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, hymns, marches, vaudeville song, and dance music. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major form of musical expression in traditional and popular music. Jazz is characterized by swing and blue notes, complex chords, call and response vocals, polyrhythms and improvisation.

As jazz spread around the world, it drew on national, regional, and local musical cultures, which gave rise to different styles. New Orleans jazz began in the early 1910s, combining earlier brass band marches, French quadrilles, biguine, ragtime and blues with collective polyphonic improvisation. However, jazz did not begin as a single musical tradition in New Orleans or elsewhere.[1] In the 1930s, arranged dance-oriented swing big bands, Kansas City jazz (a hard-swinging, bluesy, improvisational style), and gypsy jazz (a style that emphasized musette waltzes) were the prominent styles. Bebop emerged in the 1940s, shifting jazz from danceable popular music toward a more challenging "musician's music" which was played at faster tempos and used more chord-based improvisation. Cool jazz developed near the end of the 1940s, introducing calmer, smoother sounds and long, linear melodic lines.[2]

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.[1]

The Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance. The Jazz Age is often referred to in conjunction with the Roaring Twenties, and overlapped in significant cross-cultural ways with the Prohibition Era. The movement was largely affected by the introduction of radios nationwide. During this time, the Jazz Age was intertwined with the developing youth culture. The movement also helped introduce the European jazz movement.

Lindy Hop is an American dance which was born in the African-American communities of Harlem, New York City, in 1928 and has evolved since then. It was very popular during the swing era of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Lindy is a fusion of many dances that preceded it or were popular during its development but is mainly based on jazz, tap, breakaway, and Charleston. It is frequently described as a jazz dance and is a member of the swing dance family.

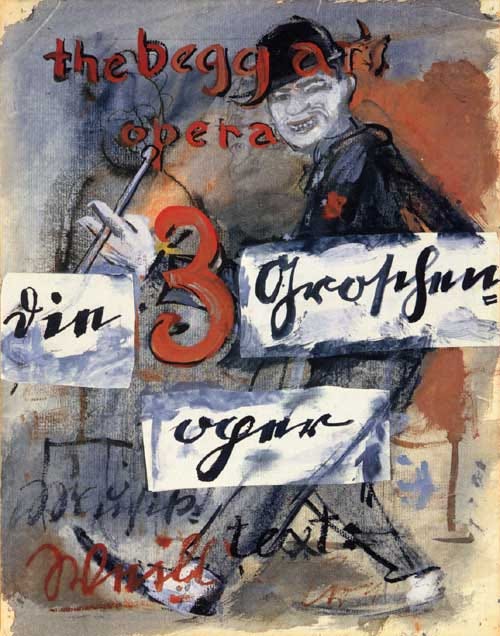

Bertold Brecht, (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a playwright in Munich and moved to Berlin in 1924, where he wrote The Threepenny Opera with Kurt Weill and began a life-long collaboration with the composer Hanns Eisler. Immersed in Marxist thought during this period, he wrote didactic Lehrstücke and became a leading theoretician of epic theatre (which he later preferred to call "dialectical theatre") and the Verfremdungseffekt.

Aby Warburg (June 13, 1866 – October 26, 1929) was a German art historian and cultural theorist who founded the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (Library for Cultural Studies), a private library, which was later moved to the Warburg Institute, London. At the heart of his research was the legacy of the classical world, and the transmission of classical representation, in the most varied areas of Western culture through to the Renaissance.

Mnemosyne Atlas, In December 1927, Warburg started to compose a work in the form of a picture atlas named Mnemosyne. It consisted of 40 wooden panels covered with black cloth, on which were pinned nearly 1,000 pictures from books, magazines, newspapers and other daily life sources.[11] These pictures were arranged according to different themes:

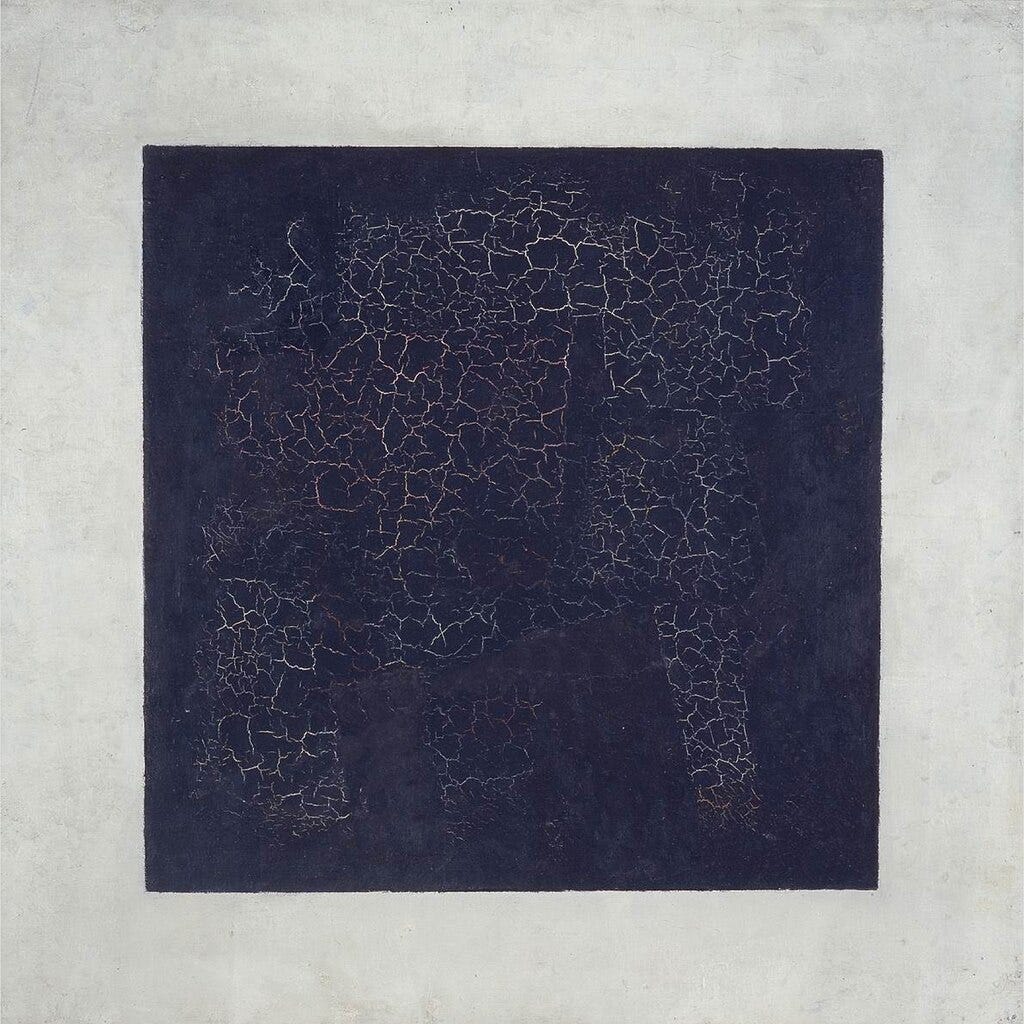

Black Square (1915), by Kazimir Malevich

Art and politics in propaganda and the Soviet

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its end as late as 1960. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that flourished at the time; including Suprematism, Constructivism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Zaum, Imaginism, and Neo-primitivism.[2][3][4][5]

In Ukraine, many of the artists who were born, grew up or were active in what is now Belarus and Ukraine (including Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Vladimir Tatlin, David Burliuk, Alexander Archipenko), are also classified in the Ukrainian avant-garde.[6]

The Russian avant-garde reached its creative and popular height in the period between the Russian Revolution of 1917 and 1932, at which point the ideas of the avant-garde clashed with the newly emerged state-sponsored direction of Socialist Realism.[7]

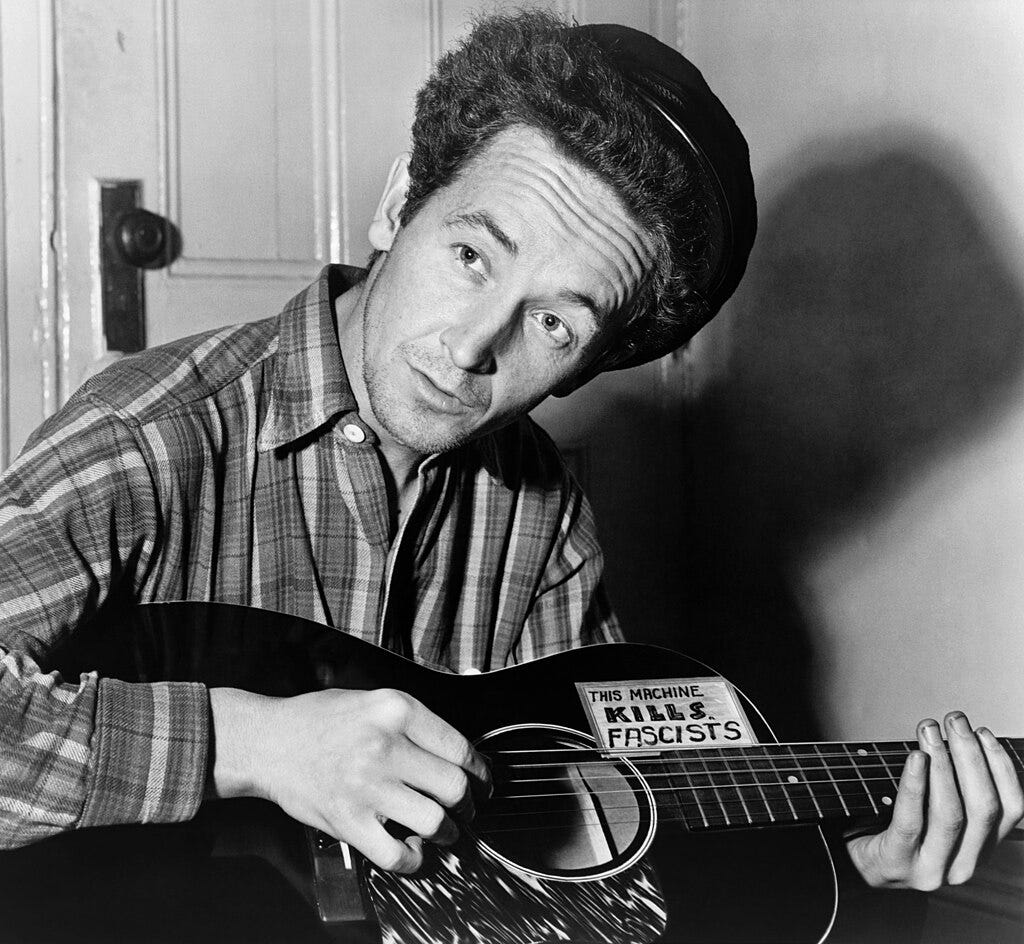

“THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”

Folk music and Woody Guthrie was an American singer-songwriter and composer who was one of the most significant figures in American folk music. His work focused on themes of American socialism and anti-fascism. He inspired several generations both politically and musically with songs such as "This Land Is Your Land".[5][6][7]

“Make it New,” modernism, Ezra Pound

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented with literary form and expression, as exemplified by Ezra Pound's maxim to "Make it new".[1] This literary movement was driven by a conscious desire to overturn traditional modes of representation and express the new sensibilities of the time.[2] The immense human costs of the First World War saw the prevailing assumptions about society reassessed,[3] and much modernist writing engages with the technological advances and societal changes of modernity moving into the 20th century. In Modernist Literature, Mary Ann Gillies notes that these literary themes share the "centrality of a conscious break with the past", one that "emerges as a complex response across continents and disciplines to a changing world".[4]

Berlin between the Wars

(German: Entartete Kunst) was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, was removed from state-owned museums and banned in Nazi Germany on the grounds that such art was an "insult to German feeling", un-German, Freemasonic, Jewish, or Communist in nature. Those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions that included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce art.

Degenerate Art also was the title of a 1937 exhibition held by the Nazis in Munich, consisting of 650 modernist artworks that the Nazis had taken from museums, that were poorly hung alongside graffiti and text labels mocking the art and the artists.[1] Designed to inflame public opinion against modernism, the exhibition subsequently traveled to several other cities in Germany and Austria.

While modern styles of art were prohibited, the Nazis promoted paintings and sculptures that were traditional in manner and that exalted the "blood and soil" values of racial purity, militarism, and obedience. Similar restrictions were placed upon music, which was expected to be tonal and free of any jazz influences; disapproved music was termed degenerate music. Films and plays were also censored.[2]

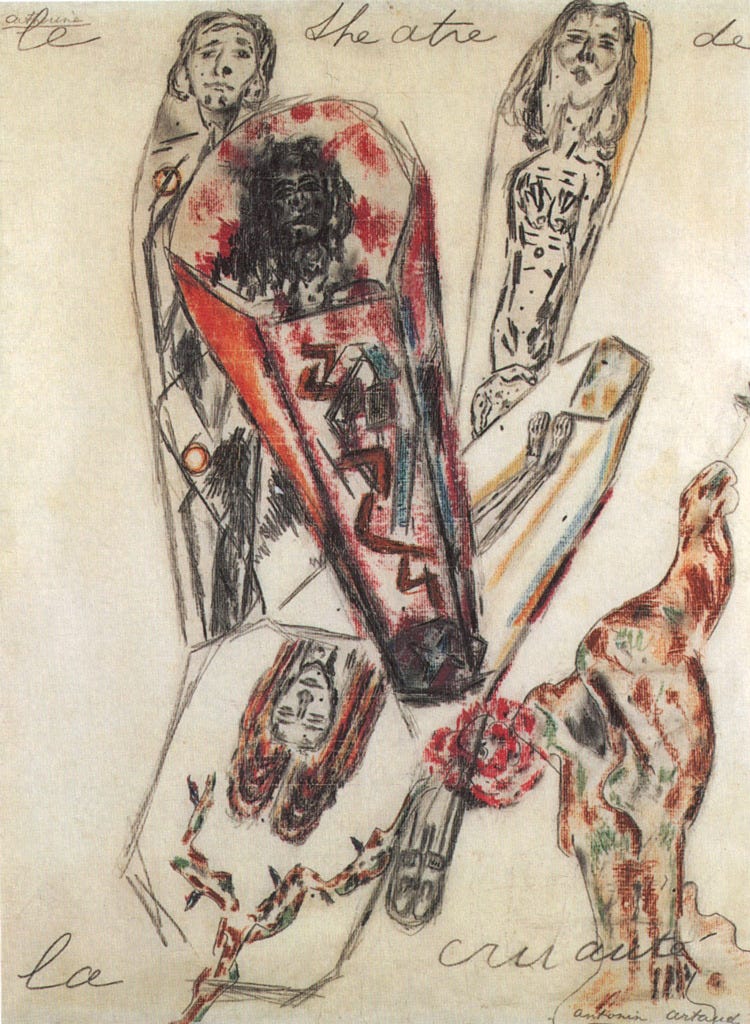

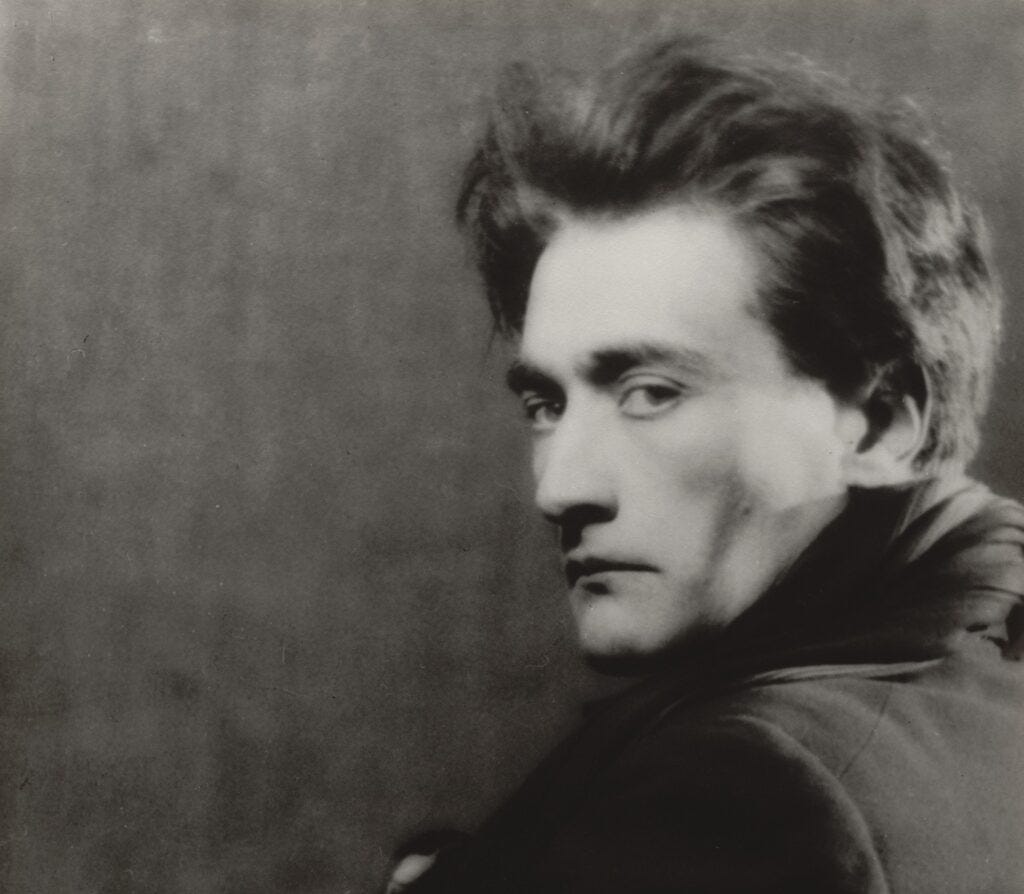

Artaud, Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud, better known as Antonin Artaud (pronounced [ɑ̃tɔnɛ̃ aʁto]; 4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French writer, poet, dramatist, visual artist, essayist, actor and theatre director.[1][2] He is widely recognized as a major figure of the European avant-garde. In particular, he had a profound influence on twentieth-century theatre through his conceptualization of the

Theatre of Cruelty. Known for his raw, surreal and transgressive work, his texts explored themes from the cosmologies of ancient cultures, philosophy, the occult, mysticism and indigenous Mexican and Balinese practices.[6][7][8][9]

Improv and Bebop, Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early-to-mid-1940s in the United States. The style features compositions characterized by a fast tempo (usually exceeding 200 bpm), complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerous changes of key, instrumental virtuosity, and improvisation based on a combination of harmonic structure, the use of scales and occasional references to the melody. Charlie Parker; tenor sax players Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, and James Moody; clarinet player Buddy DeFranco; trumpeters Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, and Dizzy Gillespie; pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk; electric guitarist Charlie Christian; and drummers Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, and Art Blakey.

New Modern Art Movements after WWII: Figuratifs, Abstract Expressionism, Art Brut, Arte Povera, Color Field painting, Tachisme, COBRA, Conceptual Art, De-collage, Neo-Dada, Figurative Expressionism, Feminist Art, Fluxus, Happenings, Kinetic art, Land art, Minimal art, Postminimalism, Op art, Photorealism, Pop art, Shaped canvas, Soviet art, Spatialism, Video Art.

Banned books: Ulysses, Allen Ginsberg, Howl, 1984, Naked Lunch

The Beat Generation was a literary subculture movement started by a group of authors whose work explored and influenced American culture and politics in the post-World War II era.[1] The bulk of their work was published and popularized by Silent Generationers in the 1950s, better known as Beatniks. The central elements of Beat culture are the rejection of standard narrative values, making a spiritual quest, the exploration of American and Eastern religions, the rejection of economic materialism, explicit portrayals of the human condition, experimentation with psychedelic drugs, and sexual liberation and exploration. The core group of Beat Generation authors—Herbert Huncke, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Lucien Carr, and Kerouac—met in 1944 in and around the Columbia University campus in New York City.

The Beat Hotel, The hotel gained fame through the extended "family" of beat writers and artists who stayed there from the late 1950s to the early 1960s in a ferment of creativity. Gregory Corso was introduced to the hotel by painter and resident Guy Harloff in 1957.[4] In September of that year, Corso would be joined by Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. William S. Burroughs, Derek Raymond, and Harold Norse, as well as Sinclair Beiles would follow. It was here that Burroughs completed the text of Naked Lunch [5] and began his lifelong collaboration with Brion Gysin. It was also where Ian Sommerville became Burroughs' "systems advisor" and lover. Gysin introduced Burroughs to the cut-up technique and with Sommerville they experimented with a "dream machine" and audio tape cut-ups. Here Norse wrote a novel Beat Hotel using cut-up techniques.[6] Ginsberg wrote a part of his moving and mature poem Kaddish at the hotel, and Corso wrote the mushroom cloud-shaped poem Bomb.

City Lights is an independent bookstore-publisher combination in San Francisco, California, that specializes in world literature, the arts, and progressive politics. It also houses the nonprofit City Lights Foundation, which publishes selected titles related to San Francisco culture. It was founded in 1953 by poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter D. Martin[2] (who left two years later). Both the store and the publishers became widely known following the obscenity trial of Ferlinghetti for publishing Allen Ginsberg's influential collection Howl and Other Poems (City Lights, 1956). Nancy Peters started working there in 1971 and retired as executive director in 2007. In 2001, City Lights was made an official historic landmark. City Lights is located at 261 Columbus Avenue. While formally located in Chinatown, it self-identifies as part of immediately adjacent North Beach.

Burroughs and Gysin, dream machine, the cut-ups

The Dreamachine (a contraction of Dream Machine), invented in 1959 by Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, is a stroboscopic flickering light art device that produces eidetic visual stimuli.

In its original form, a Dreamachine is a work of light art made from a cylinder with regularly spaced shapes cut out of its sides. The cylinder is then placed on a record turntable and rotated, depending on the scale, at either 78 or 45 revolutions per minute. A light bulb is suspended in the center of the cylinder with the rotation speed making light emanate from the holes at a consistently pulsating frequency range of 8–13 flickers per second. It is meant to be looked at through closed eyelids, upon which moving yantra-like mandala visual patterns emerge, and an alpha wave mental state is induced. The frequency of the pulsations corresponds to the electrical oscillations normally present in the human brain while relaxing. In 1996, the Los Angeles Times deemed David Woodard's iteration of the Dreamachine "the most interesting object" in Burroughs' major visual retrospective Ports of Entry at LACMA.[1][2] In a 2019 critical study, Raj Chandarlapaty, a scholar of the Beat movement, revisits and examines Woodard's "idea-shattering" approach to the Dreamachine.[3]

The cut-up technique (or découpé in French) is an aleatory narrative technique in which a written text is cut up and rearranged to create a new text. The concept can be traced to the Dadaists of the 1920s, but it was developed and popularized in the 1950s and early 1960s, especially by writer William Burroughs. It has since been used in a wide variety of contexts.

Harry Smith, experimental film, Anthology of Folk Music (May 29, 1923 – November 27, 1991) was an American polymath, who was credited variously as an artist, experimental filmmaker, bohemian, mystic, record collector, hoarder, student of anthropology and a Neo-Gnostic bishop. Smith was an important figure in the Beat Generation scene in New York City, and his activities, such as his use of mind-altering substances and interest in esoteric spirituality, anticipated aspects of the Hippie movement. Besides his films, such as his full length cutout animated film Heaven and Earth Magic (1962), Smith is also remembered for his influential Anthology of American Folk Music, drawn from his extensive collection of out-of-print commercial 78 rpm recordings.

A prepared piano is a piano that has had its sounds temporarily altered by placing bolts, screws, mutes, rubber erasers, and/or other objects on or between the strings. Its invention is usually traced to John Cage, who used the technique in his dance music for Bacchanale (1940), created for a performance in a Seattle venue that lacked sufficient space for a percussion ensemble. Cage has cited Henry Cowell as an inspiration for developing piano extended techniques, involving strings within a piano being manipulated instead of the keyboard. Typical of Cage's practice, as summed up in the Sonatas and Interludes (1946–1948), is that each key of the piano has its own characteristic timbre, and that the original pitch of the string will not necessarily be recognizable. Further variety is available with use of the una corda pedal.

John Cage, (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde. Critics have lauded him as one of the most influential composers of the 20th century.[1][2][3][4] He was also instrumental in the development of modern dance, mostly through his association with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who was also Cage's romantic partner for most of their lives.[5][6]

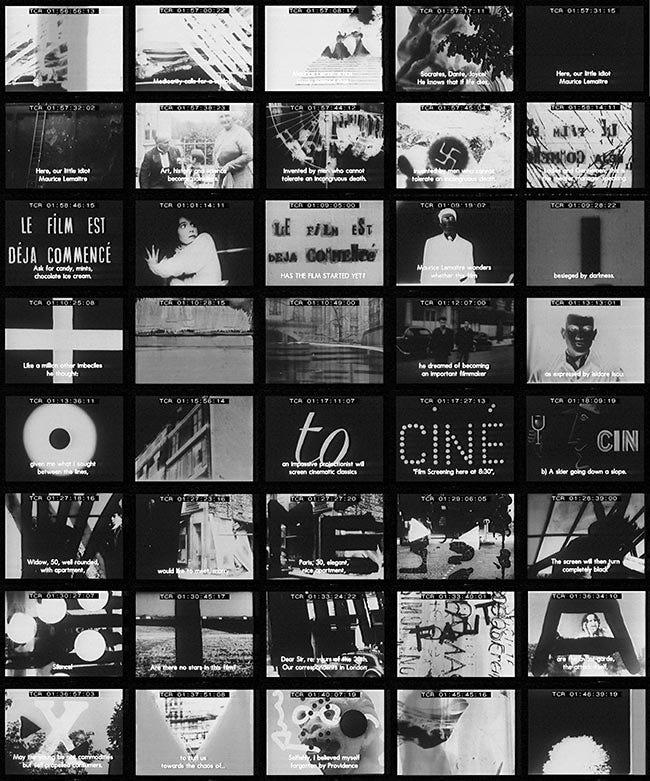

Lettrist, The Letterist International (LI) was a Paris-based collective of radical artists and cultural theorists between 1952 and 1957. It was created by Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman rejoined by Jean-Louis Brau and Serge Berna as a schism from Isidore Isou's Lettrist group. The group went on to join others in forming the Situationist International, taking some key techniques and ideas with it.[1]

The Society of the Spectacle (French: La société du spectacle) is a 1967 work of philosophy and Marxist critical theory by Guy Debord where he develops and presents the concept of the Spectacle. The book is considered a seminal text for the Situationist movement. Debord published a follow-up book Comments on the Society of the Spectacle in 1988.[1]

The Paris Review is a quarterly English-language literary magazine established in Paris in 1953[1] by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton. In its first five years, The Paris Review published works by Jack Kerouac, Philip Larkin, V. S. Naipaul, Philip Roth, Terry Southern, Adrienne Rich, Italo Calvino, Samuel Beckett, Nadine Gordimer, Jean Genet, and Robert Bly.

Camus, Albert Camus (/kæmˈuː/[2] kam-OO; French: [albɛʁ kamy] ⓘ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, journalist, and political activist. He was the recipient of the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His works include The Stranger, The Plague, The Myth of Sisyphus, The Fall, and The Rebel.

Theater of the Absurd, Critic Martin Esslin coined the term in his 1960 essay "The Theatre of the Absurd", which begins by focusing on the playwrights Samuel Beckett, Arthur Adamov, and Eugène Ionesco. Esslin says that their plays have a common denominator—the "absurd", a word that Esslin defines with a quotation from Ionesco: "absurd is that which has not purpose, or goal, or objective."[2][3] The French philosopher Albert Camus, in his 1942 essay "Myth of Sisyphus", describes the human situation as meaningless and absurd.[4]

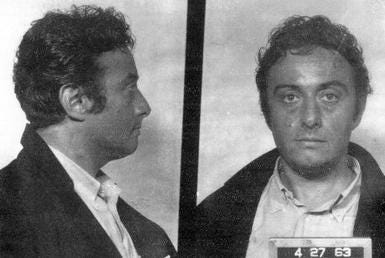

Comedy, Lenny Bruce, was an American stand-up comedian, social critic, and satirist. He was renowned for his open, free-wheeling, and critical style of comedy which contained satire, politics, religion, sex, and vulgarity.[2] His 1964 conviction in an obscenity trial was followed by a posthumous pardon in 2003

Pop Culture - “the new”

Play Boy

Betty Page

Blue Movies

Swingers

Wife Swapping, and bondage

Rock n Roll

Car Art

Hot Rods

Motorcycle Gangs

Cartoons

Mad Magazine

Hells Angels

The Motion Picture Association film rating system is used in the United States and its territories to rate a motion picture's suitability for certain audiences based on its content. The system and the ratings applied to individual motion pictures are the responsibility of the Motion Picture Association (MPA), previously known as the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) from 1945 to 2019. The MPA rating system is a voluntary scheme that is not enforced by law; films can be exhibited without a rating, although most theaters refuse to exhibit non-rated or NC-17 rated films. Non-members of the MPA may also submit films for rating.[1] Other media, such as television programs, music and video games, are rated by other entities such as the TV Parental Guidelines, the RIAA and the ESRB, respectively. Introduced in 1968,[2] following the Hays Code of the classical Hollywood cinema era, the MPA rating system is one of various motion picture rating systems that are used to help parents decide what films are appropriate for their children. It is administered by the Classification & Ratings Administration (CARA), an independent division of the MPA.[3]

Butoh, is a form of Japanese dance theatre that encompasses a diverse range of activities, techniques and motivations for dance, performance, or movement. Following World War II, butoh arose in 1959 through collaborations between its two key founders, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. The art form is known to "resist fixity"[1] and is difficult to define; notably, founder Hijikata Tatsumi viewed the formalisation of butoh with "distress".[2] Common features of the art form include playful and grotesque imagery, taboo topics, and extreme or absurd environments. It is traditionally performed in white body makeup with slow hyper-controlled motion. However, with time butoh groups are increasingly being formed around the world, with their various aesthetic ideals and intentions.

Pierre Henry, was born in Paris, France,[3] and began experimenting at the age of 15 with sounds produced by various objects. He became fascinated with the integration of noise into music, now called noise music. He studied with Nadia Boulanger, Olivier Messiaen, and Félix Passerone at the Conservatoire de Paris from 1938 to 1948.[4]

Between 1949 and 1958, Henry worked at the Club d'Essai studio at RTF, which had been founded by Pierre Schaeffer in 1942.[4] During this period, he wrote the 1950 piece Symphonie pour un homme seul, in cooperation with Schaeffer. It is an important early example of musique concrète. Henry also composed the first musique concrète track to appear in a commercial film: the 1952 short film Astrologie ou le miroir de la vie by Jean Grémillon. Henry also scored numerous additional films and ballets.

Musique Concrete, is a type of music composition that utilizes recorded sounds as raw material.[1] Sounds are often modified through the application of audio signal processing and tape music techniques, and may be assembled into a form of sound collage

Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer (English pronunciation: /piːˈɛər ˈhɛnriː məˈriː ˈʃeɪfər/ ⓘ, French pronunciation: [ʃɛfɛʁ]; 14 August 1910 – 19 August 1995)[1] was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His innovative work in both the sciences—particularly communications and acoustics—and the various arts of music, literature and radio presentation after the end of World War II, as well as his anti-nuclear activism and cultural criticism garnered him widespread recognition in his lifetime.

Schaeffer is most widely and currently recognized for his accomplishments in electronic and experimental music,[2] at the core of which stands his role as the chief developer of a unique and early form of avant-garde music known as musique concrète.[3] The genre emerged in Europe from the utilization of new music technology developed in the post-war era, following the advance of electroacoustic and acousmatic music.

1962, Yvonne Rainer, No manifesto https://1000manifestos.com/yvonne-rainer-no-manifesto/

Yvonne Rainer (born November 24, 1934) is an American dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker, whose work in these disciplines is regarded as challenging and experimental.[1] Her work is sometimes classified as minimalist art. Rainer currently lives and works in New York.[2]

Judson Dance Theater was a collective of dancers, composers, and visual artists who performed at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, Manhattan New York City between 1962 and 1964. The artists involved were avant garde experimentalists who rejected the confines of Modern dance practice and theory.

Free Jazz, Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

Free jazz, or free form in the early to mid-1970s,[1] is a style of avant-garde jazz or an experimental approach to jazz improvisation that developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when musicians attempted to change or break down jazz conventions, such as regular tempos, tones, and chord changes. Musicians during this period believed that the bebop and modal jazz that had been played before them was too limiting, and became preoccupied with creating something new. The term "free jazz" was drawn from the 1960 Ornette Coleman recording Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. Europeans tend to favor the term "free improvisation". Others have used "modern jazz", "creative music", and "art music".

The ambiguity of free jazz presents problems of definition. Although it is usually played by small groups or individuals, free jazz big bands have existed. Although musicians and critics claim it is innovative and forward-looking, it draws on early styles of jazz and has been described as an attempt to return to primitive, often religious, roots. Although jazz is an American invention, free jazz musicians drew heavily from world music and ethnic music traditions from around the world. Sometimes they played African or Asian instruments, unusual instruments, or invented their own. They emphasized emotional intensity and sound for its own sake, exploring timbre.

Le Sony'r Ra[2] (born Herman Poole Blount, May 22, 1914 – May 30, 1993), better known as Sun Ra, was an American jazz composer, bandleader, piano and synthesizer player, and poet known for his experimental music, "cosmic" philosophy, prolific output, and theatrical performances. For much of his career, Ra led The Arkestra, an ensemble with an ever-changing name and flexible line-up.

Fluxus, was an international, interdisciplinary community of artists, composers, designers and poets during the 1960s and 1970s who engaged in experimental art performances which emphasized the artistic process over the finished product.[1][2] Fluxus is known for experimental contributions to different artistic media and disciplines and for generating new art forms. These art forms include intermedia, a term coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins;[3][4][5][6] conceptual art, first developed by Henry Flynt,[7][8] an artist contentiously associated with Fluxus; and video art, first pioneered by Nam June Paik and Wolf Vostell.[9][10][11] Dutch gallerist and art critic Harry Ruhé describes Fluxus as "the most radical and experimental art movement of the sixties". Yoko Onos loft, Tony Conrad.

Charlotte Moorman & Nam June Paik

Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York

In 1963 Moorman founded the Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York,[11] which presented the experimental music of the Fluxus group and Happenings alongside performance, kinetic art, and video art.[12] Despite the event's title the festival was not held annually. There were fifteen festivals from 1963 to 1980.[11] In addition, the festivals were often organized at unique locations such as Shea Stadium, Grand Central Station, the World Trade Center, and the Staten Island Ferry.[12]

As well as being a star performer of avant-garde pieces, she was an effective spokesperson and negotiator for advanced art, charming the bureaucracies of New York and other major cities into co-operating and providing facilities for controversial and challenging performances. The years of the Avant Garde Festival marked a period of unparalleled understanding and good relations between advanced artists and local authorities.[6] Friend and artist Jim McWilliams' created numerous memorable pieces for her to perform at the New York Avant Garde Festivals, including Sky Kiss which involved her hanging suspended from helium-filled weather balloons for the Sixth Avant Garde Festival, and The Intravenous Feeding of Charlotte Moorman for the 1973 edition.[13]

Collaborations with Nam June Paik

At the Second Avant Garde Festival, Moorman convinced Karlheinz Stockhausen to restage his performance piece, Originale, using his original collaborator Nam June Paik.[14] This meeting began the decades-long collaboration between Moorman and Paik in which they fused sculpture, performance, music and art.[7] In addition, Paik created many works specifically for Moorman, including TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969) and TV-Cello (1971).[14]

On February 9, 1967, Moorman achieved widespread notoriety for her performance of Paik's Opera Sextronique at the Film-Makers Cinematheque in New York City.[15] For this performance, Moorman was to perform movements on the cello in various states of nudity.[15] In the program for the performance, Paik wrote: "The purge of sex under the excuse of being 'serious' exactly undermines the so-called 'seriousness' of music as a classical art, ranking with literature and painting."[15] During the first movement, Moorman played Elegy by the French composer Jules Massenet in the dark while wearing a bikini that had blinking lights.[15] For the second movement, she played International Lullaby by Max Mathews while wearing a black skirt, but while being topless, and was arrested mid-performance by three plainclothes police officers.[15] She was not able to return to perform the last two movements of the work.[15] As a result of Opera Sextronique, Moorman was charged with indecent exposure, though her penalty was later suspended, and gained nationwide fame as the "topless cellist."[4] She was also fired from the American Symphony Orchestra.[11] For her court trial, Moorman and Paik restaged and filmed the first two movements of Opera Sextronique with the filmmaker Jud Yalkut, though the film was not permitted to be shown in court.[15]

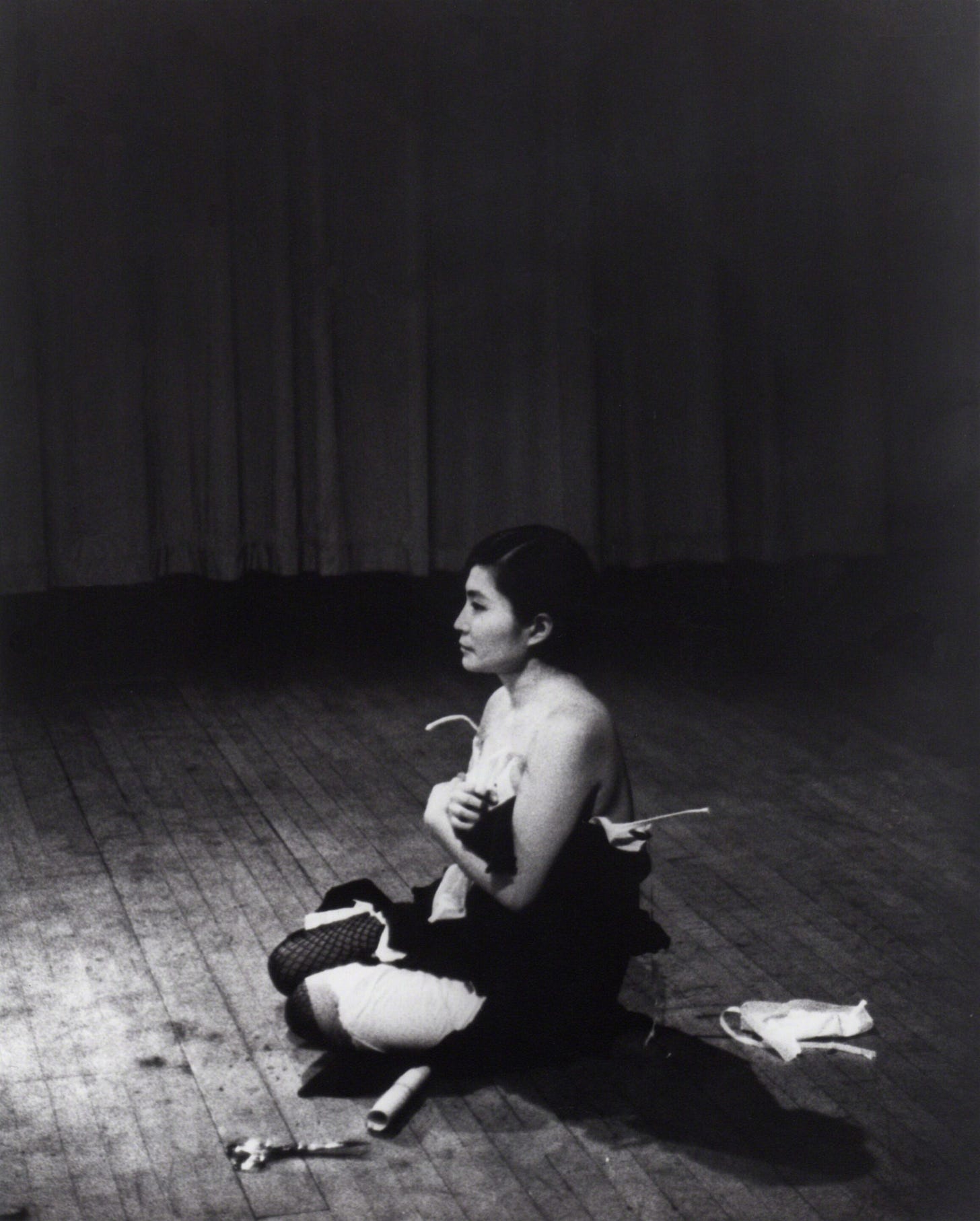

Yoko Ono grew up in Tokyo and moved to New York City in 1952 to join her family. She became involved with New York City's downtown artists scene in the early 1960s, which included the Fluxus group, and became well known in 1969 when she married English musician John Lennon of the Beatles, with whom she would subsequently record as a duo in the Plastic Ono Band. The couple used their honeymoon as a stage for public protests against the Vietnam War. Ono has often been associated with the Fluxus group, a loose association of Dada-inspired avant-garde artists which was founded in the early 1960s by Lithuanian-American artist George Maciunas. Maciunas admired and enthusiastically promoted her work, and gave Ono her first solo exhibition at his AG Gallery in New York in 1961. He formally invited Ono to join Fluxus, but she declined because she wanted to remain independent.[26] However, she did collaborate with Maciunas,[27] Charlotte Moorman, George Brecht, and the poet Jackson Mac Low, among others associated with the group.[28]

Cut Piece, a performance piece by Yoko Ono in which the audience is invited to cut off her clothing. This version was staged at Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, 21 March 1965. Still taken from a film by Albert and David Maysles

La Monte Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American composer, musician, and performance artist recognized as one of the first American minimalist composers and a central figure in Fluxus and post-war avant-garde music.[1][2][3] He is best known for his exploration of sustained tones, beginning with his 1958 composition Trio for Strings.[4] His compositions have called into question the nature and definition of music, most prominently in the text scores of his Compositions 1960.[5] While few of his recordings remain in print, his work has inspired prominent musicians across various genres, including avant-garde, rock, and ambient music.[6]

The Film-Makers' Cooperative (a.k.a. The New American Cinema Group, Inc.) is an artist-run, non-profit organization founded in 1961 in New York City by Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Shirley Clarke, Stan Brakhage, Jack Smith, Lionel Rogosin, Gregory Markopoulos, Lloyd Michael Williams, and other filmmakers, for the distribution, education, and exhibition of avant-garde films and alternative media.

Kenneth Anger (born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer, February 3, 1927 – May 11, 2023) was an American underground experimental filmmaker, actor, and author. Working exclusively in short films, he produced almost 40 works beginning in 1937, nine of which have been grouped together as the "Magick Lantern Cycle".[1] Anger's films variously merge surrealism with homoeroticism and the occult, and have been described as containing "elements of erotica, documentary, psychodrama, and spectacle".[2] He has been called "one of America's first openly gay filmmakers",[3] with several films released before homosexuality was legalized in the U.S. Anger also explored occult themes in many of his films; he was fascinated by the English occultist Aleister Crowley and an adherent of Thelema, the religion Crowley founded.

LSD and other psychedelics were adopted by, and became synonymous with, the counterculture movement due to their perceived ability to expand consciousness.

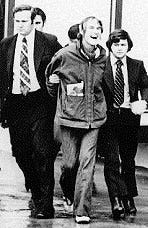

Timothy Leary (October 22, 1920 – May 31, 1996) was an American psychologist and author known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs.[2] Evaluations of Leary are polarized, ranging from bold oracle to publicity hound. According to poet Allen Ginsberg, he was "a hero of American consciousness", and writer Tom Robbins called him a "brave neuronaut".[3] During the 1960s and 1970s, Leary was arrested 36 times.[4] President Richard Nixon allegedly described him as "the most dangerous man in America".[B]

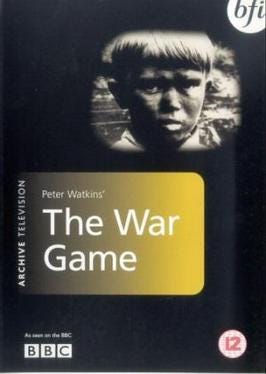

Peter Watkins (born 29 October 1935) is an English film and television director. He was born in Norbiton, Surrey, lived in Sweden, Canada and Lithuania for many years, and now lives in France. He is one of the pioneers of docudrama. His films present pacifist and radical ideas in a nontraditional style. He mainly concentrates his works and ideas around the mass media and our relation/participation to a movie or television documentary. Nearly all of Watkins' films have used a combination of dramatic and documentary elements to dissect historical occurrences or possible near future events. The first of these, Culloden, portrayed the Jacobite uprising of 1745 in a documentary style, as if television reporters were interviewing the participants and accompanying them into battle; a similar device was used in his biographical film Edvard Munch. La Commune reenacts the Paris Commune days using a large cast of French non-actors. The War Game (1966) depicts the aftermath of a hypothetical nuclear attack on Great Britain. His other notable works include Edvard Munch, a biographical film of the painter of the same name, and The Journey, a 14-hour essay film about nuclear disarmament.

The British Film Institute writes "in an age when the media stranglehold on both our lives and the means by which we communicate is ever tightening, [Watkins] films remain a vital tool for considering new forms of image-making and a vibrant and engaging force in their own right."[1]

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon and political movement that developed in the Western world during the mid-20th century. It began in the mid-1960s,[3] and continued through the early 1970s.[3] It is often synonymous with cultural liberalism and with the various social changes of the decade. The effects of the movement[3] have been ongoing to the present day. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the civil rights movement in the United States had made significant progress, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and with the intensification of the Vietnam War that same year, it became revolutionary to some.[4][5][6] As the movement progressed, widespread social tensions also developed concerning other issues, and tended to flow along generational lines regarding respect for the individual, human sexuality, women's rights, traditional modes of authority, rights of people of color, end of racial segregation, experimentation with psychoactive drugs, and differing interpretations of the American Dream. Many key movements related to these issues were born or advanced within the counterculture of the 1960s.[7]

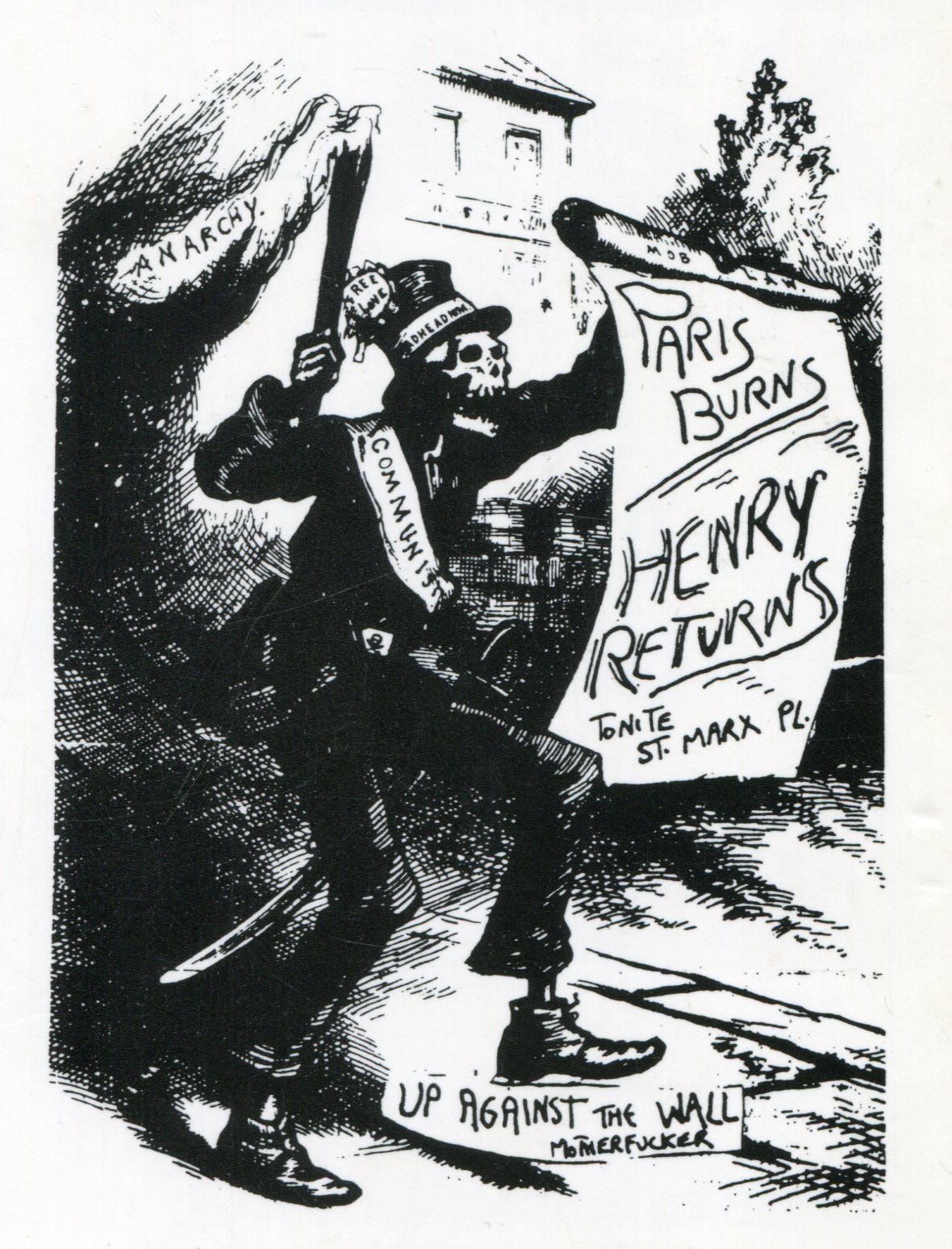

Black Mask, & Up Against The Wall Mother Fucker, , often shortened as The Motherfuckers or UAW/MF, was a Dadaist and Situationist anarchist affinity group based in New York City. This "street gang with analysis" was famous for its Lower East Side direct action.

1967 – Forced their way into The Pentagon during an anti-war protest.[5]

1967 – Flung blood, eggs and stones at U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk who was attending a Foreign Policy Association event in New York.[6]

January, 1968 – "Assassinated" poet Kenneth Koch (using blanks).[7]

February, 1968 - Dumped uncollected refuse from the Lower East Side into the fountain at Lincoln Center on the opening night of a gala "bourgeois cultural event" during a NYC garbage strike (an event documented in the Newsreel film Garbage).[8][9]

1968 – Organized and produced free concert nights in the Fillmore East after successfully demanding that owner Bill Graham give the community the venue for a series of weekly free concerts. These "Free Nights" were short-lived as the combined forces of NY City Hall, the police, and Graham terminated the arrangement.[10]

December 12, 1968 - Created a ruckus at the Boston Tea Party: after the MC5 opened for the Velvet Underground one of the Motherfuckers got on stage and started haranguing the audience, directing them to "...burn this place down and take to the streets...". This got "The Five" banned from the venue.[11]

December 18, 1968 - Rioted at an MC5 show at the Fillmore East. Some "beat (Graham) with a chain and broke his nose". This got the Detroit band banned from all venues controlled by Graham and his friends.[12]

Cut the fences at Woodstock, allowing thousands to enter for free.[5]

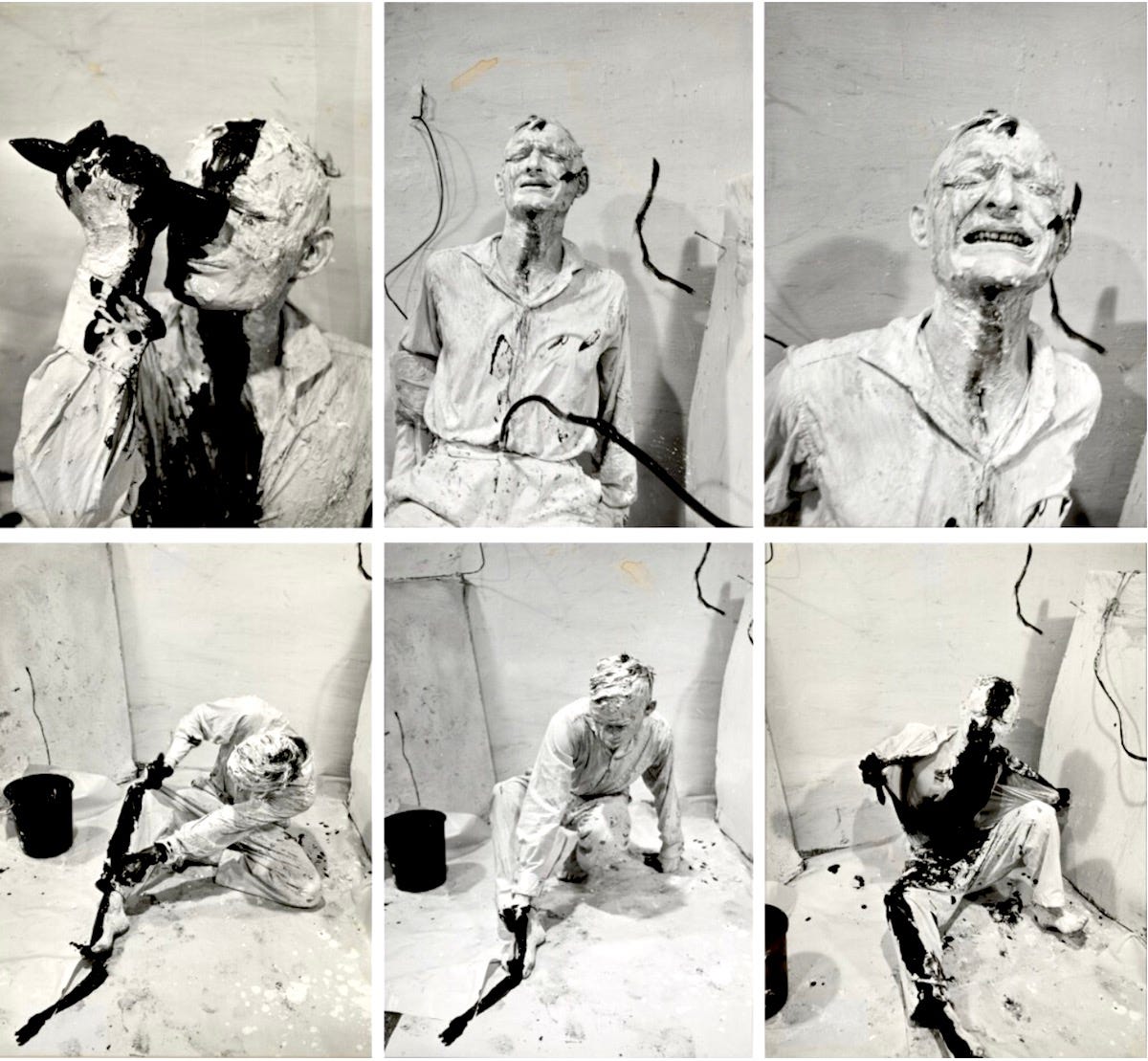

Hermann Nitsch, Born in Vienna, Nitsch received training in painting when he studied at the Wiener Graphische Lehr-und Versuchanstalt, during which time he was drawn to religious art.[2][3] He is associated with the Vienna Actionists—a loosely affiliated group of Austrian artists interested in transgressive themes and the centrality of the body in their artwork, which also includes Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler.[4]

Nitsch's abstract 'splatter' paintings, like his performance pieces were inspired by his neutral perspective on humanity and being human. In the 1950s, Nitsch conceived of the Orgien Mysterien Theater (which roughly translates as Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries or The Orgiastic Mystery Theater) and staged nearly 100 performances between 1962 and 1998.[4]

Viennese Actionism, was a short-lived art movement in the late 20th-century that spanned the 1960s into the 1970s.[1] It is regarded as part of the independent efforts made during the 1960s to develop the issues of performance art, Fluxus, happening, action painting, and body art. Its main participants were Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, Hermann Nitsch, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler. Others involved in the movement include Anni Brus, Heinz Cibulka and Valie Export. Many of the Actionists have continued their artistic work independently of Viennese Actionism movement.

Gunter Brus, Brus was a co-founder in 1964 of Viennese Actionism (German: Wiener Aktionismus) with Otto Muehl, Hermann Nitsch, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler. His aggressively presented actionism intentionally disregarded conventions and taboos, with the intent of shocking the viewer. At the Kunst und Revolution event at the University of Vienna in 1968, Brus urinated into a glass then proceeded to cover his body in his own excrement, and during the performance Brus also sang the Austrian National Anthem while masturbating. Brus ended the piece by drinking his own urine and inducing vomiting, and was subsequently arrested. Through this piece and his other performance works, Brus hoped to reveal the still fascist essence of the nation. This performance created a public outrage at the time and the participants were dubbed by the media as uniferkel or "University Piggies." Sentenced to six months in prison after the event and subsequent public reactions, he fled to Berlin with his family and returned to Austria in 1976. Brus also was editor of the Die Schastrommel (author's edition) from 1969 on. He was involved in the NO!Art movement. In 1966 he participated in the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS) in London with fellow artists Gustav Metzger, Otto Muehl, Wolf Vostell, Yoko Ono, and others.[2]

VALIE EXPORT, With this gesture of self-determination, Export emphatically asserted her identity within the Viennese art scene, which was then dominated by the taboo-breaking performance art of the Vienna Actionists such as Hermann Nitsch, Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler. Of the Actionist movement, Export has said, “I was very influenced, not so much by Actionism itself, but by the whole movement in the city. It was a really great movement. We had big scandals, sometimes against the politique; it helped me to bring out my ideas.”[11] Like her male contemporaries, she subjected her body to pain and danger in actions designed to confront the growing complacency and conformism of postwar Austrian culture. But her examination of the ways in which the power relations inherent in media representations inscribe women's bodies and consciousness distinguishes Export's project as unequivocally feminist. “In these performances and in my photo work of the 60s and 70s,” Export said in a 1995 interview with Scott MacDonald, “I used a female body, generally my own, as a bearer of signs and symbols - individual, sexual, cultural - that could function within an artistic environment.”[12]

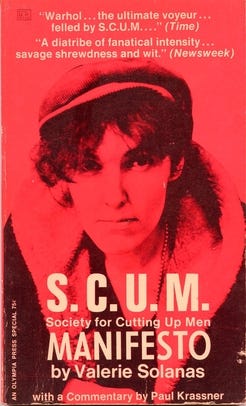

Scum Manifesto, Valerie Solanas, Valerie Jean Solanas (April 9, 1936 – April 25, 1988) was an American radical feminist known for the SCUM Manifesto, which she self-published in 1967, and for her attempt to murder artist Andy Warhol in 1968.

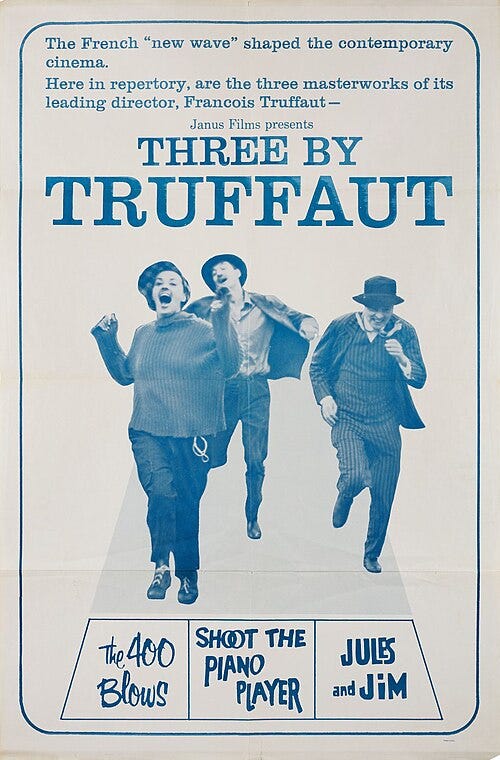

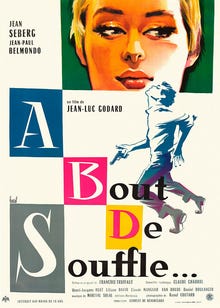

French New Wave, (French: Nouvelle Vague), also called the French New Wave, is a French art film movement that emerged in the late 1950s. The movement was characterized by its rejection of traditional filmmaking conventions in favor of experimentation and a spirit of iconoclasm. New Wave filmmakers explored new approaches to editing, visual style, and narrative, as well as engagement with the social and political upheavals of the era, often making use of irony or exploring existential themes. The New Wave is often considered one of the most influential movements in the history of cinema.

Jean Luc Godard, 3 December 1930 – 13 September 2022) was a Franco-Swiss film director, screenwriter, and film critic. He rose to prominence as a pioneer of the French New Wave film movement of the 1960s,[1] alongside such filmmakers as François Truffaut, Agnès Varda, Éric Rohmer and Jacques Demy. He was arguably the most influential French filmmaker of the post-war era.[2] According to AllMovie, his work "revolutionized the motion picture form" through its experimentation with narrative, continuity, sound, and camerawork.[2] His most acclaimed films include Breathless (1960), Vivre sa vie (1962), Contempt (1963), Band of Outsiders (1964), Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le Fou (1965), Masculin Féminin (1966), Weekend (1967) and Goodbye to Language (2014).[3][4]

Warhol Factory, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable had its beginnings in an event staged on January 13, 1966, at a dinner for the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry. This event, called "Up-Tight", included performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico, along with Malanga and Edie Sedgwick as dancers[2] and Barbara Rubin as a performance artist.[3] Inaugural shows were held at the Dom in New York City in April 1966, advertised in The Village Voice as follows: "The Silver Dream Factory Presents The Exploding Plastic Inevitable with Andy Warhol/The Velvet Underground/and Nico."[4]

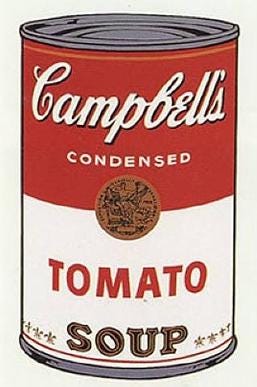

Andy Warhol, August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American visual artist, film director, producer, and leading figure in the pop art movement. His works explore the relationship between artistic expression, advertising, and celebrity culture that flourished by the 1960s, and span a variety of media, including painting, silkscreening, photography, film, and sculpture. Some of his best-known works include the silkscreen paintings Campbell's Soup Cans (1962) and Marilyn Diptych (1962), the experimental films Empire (1964) and Chelsea Girls (1966), and the multimedia events known as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966–67).

The Living Theater is an American theatre company founded in 1947 and based in New York City. It is the oldest experimental theatre group in the United States.[1][2] For most of its history it was led by its founders, actress Judith Malina and painter/poet Julian Beck. After Beck's death in 1985, company member Hanon Reznikov became co-director with Malina;[3] the two were married in 1988.[4] After Malina's death in 2015, her responsibilities were taken over by her son Garrick Maxwell Beck. The Living Theatre and its founders were the subject of the 1983 documentary Signals Through the Flames.

68 Paris Student Revolution, May 68 (French: Mai 68) was a period of widespread protests, strikes, and civil unrest in France that began in May 1968 and became one of the most significant social uprisings in modern European history. Initially sparked by student demonstrations against university conditions and government repression, the movement quickly escalated into a nationwide general strike involving millions of workers, bringing the country to the brink of revolution. The events have profoundly shaped French politics, labor relations, and cultural life, leaving a lasting legacy of radical thought and activism.

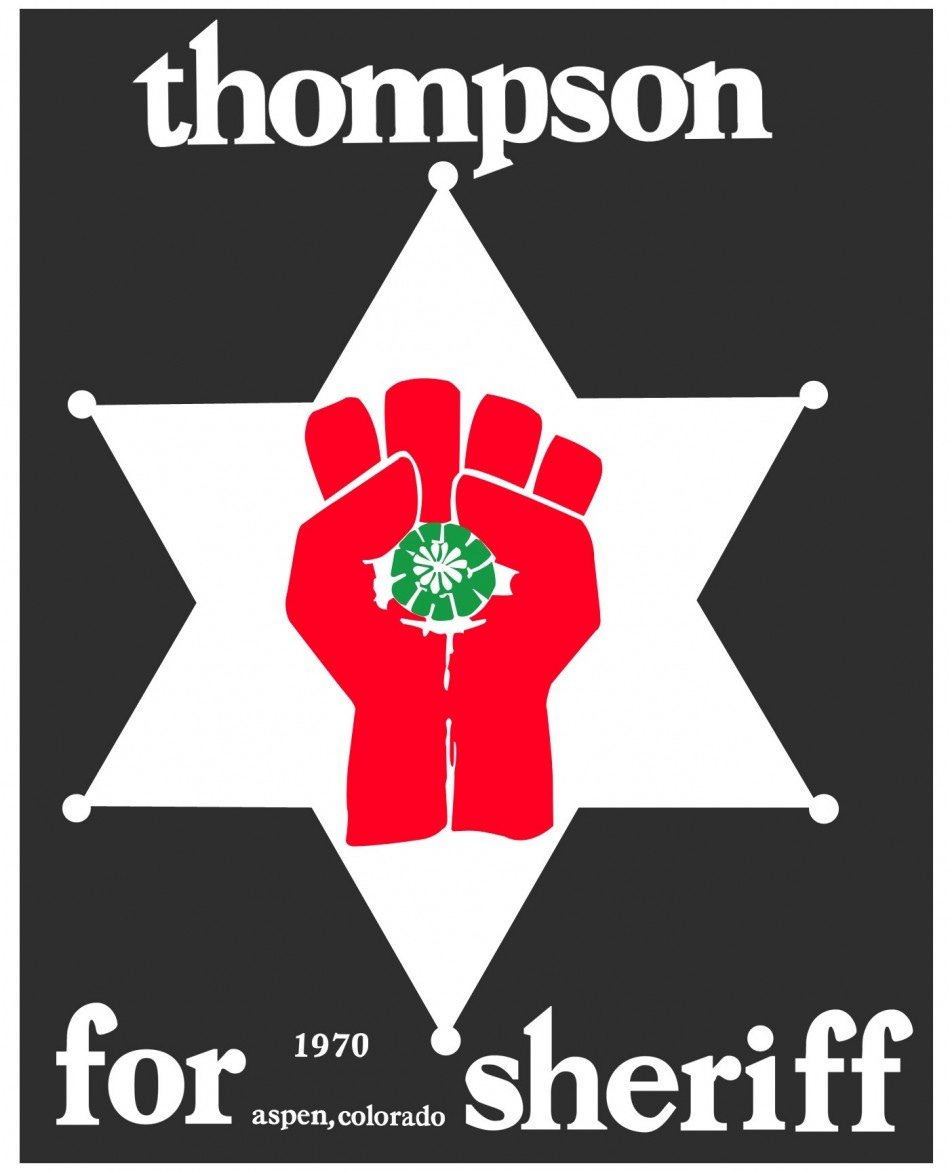

Freak Power, and the Battle for Aspen, In 1970, Thompson ran for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, as part of a group of citizens running for local offices on the "Freak Power" ticket. The platform included promoting the decriminalization of drugs (for personal use only, not trafficking, as he disapproved of profiteering), tearing up the streets and turning them into grassy pedestrian malls, banning any building so tall as to obscure the view of the mountains, disarming all police forces, and renaming Aspen "Fat City" to deter investors. Thompson, having shaved his head, referred to the crew cut-wearing Republican candidate as "my long-haired opponent".[46]

With polls showing him with a slight lead in a three-way race, Thompson appeared at Rolling Stone magazine headquarters in San Francisco with a six-pack of beer in hand, and declared to editor Jann Wenner that he was about to be elected sheriff of Aspen, Colorado, and wished to write about the "Freak Power" movement.[47] "The Battle of Aspen" was Thompson's first feature for the magazine carrying the byline "By: Dr. Hunter S. Thompson (Candidate for Sheriff)". (Thompson's "Dr" certification was obtained from a mail-order church while he was in San Francisco in the '60s.) Despite the publicity, Thompson lost the election. While carrying the city of Aspen, he garnered only 44% of the county-wide vote in what had become, after the withdrawal of the Republican candidate, a two-way race. Thompson later said that the Rolling Stone article mobilized more opposition to the Freak Power ticket than supporters.[48] The episode was the subject of the 2020 documentary film Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb. Writing of the episode more than 50 years later, Wenner wrote, "Aspen didn't get a new sheriff, but I realized that, in Hunter, I had a fellow traveler."[49]

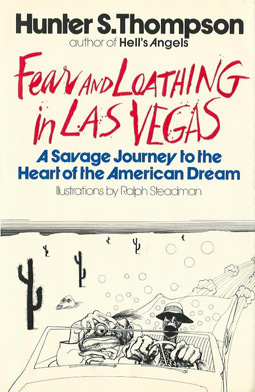

Thompson's 1971 trip to Las Vegas with Oscar Zeta Acosta (right) served as the basis for his most famous novel, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Hunter S Thompson, (July 18, 1937 – February 20, 2005) was an American journalist and author. He rose to prominence with the publication of Hell's Angels (1967), a book for which he spent a year living with the Hells Angels motorcycle club to write a first-hand account of their lives and experiences. In 1970, he wrote an unconventional article titled "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved" for Scanlan's Monthly, which further raised his profile as a countercultural figure. It also set him on the path to establishing his own subgenre of New Journalism that he called "Gonzo", a journalistic style in which the writer becomes a central figure and participant in the events of the narrative.

Thompson remains best known for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1972), a book first serialized in Rolling Stone in which he grapples with the implications of what he considered the failure of the 1960s counterculture movement. It was adapted for film twice: loosely in 1980 in Where the Buffalo Roam and explicitly in 1998 in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Jodorowsky, born 17 February 1929) is a Chilean-French avant-garde filmmaker. Best known for his 1970s films El Topo and The Holy Mountain, Jodorowsky has been "venerated by cult cinema enthusiasts" for his work which "is filled with violently surreal images and a hybrid blend of mysticism and religious provocation".[2]

"Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician[1] best known as a pioneer of the minimalist school of composition.[2] Influenced by jazz and Indian classical music, his work became notable for its innovative use of repetition, tape music techniques, and delay systems.[2] His best known works are the 1964 composition In C and the 1969 LP A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalism and important influences on experimental music, rock, and contemporary electronic music.[2]